Two very different parts of Vinh Chung’s life meet when he walks on a beach.

In an instant, the smell of sea salt takes the 36-year-old skin cancer surgeon back to his 1979 exodus from Vietnam.

Just 4 years old at the time, Vinh recalls fleeing the southern city of Ca Mau by boat from the Mekong River Delta toward the South China Sea with his parents and seven siblings.

The Chung family — ethnically Chinese — escaped the communist government’s persecution of ethnic minorities.

Once they reached the open ocean, Thai pirates stole their valuables. Their boat eventually made it to a Malaysian beach, but instead of offering asylum, soldiers held them at gunpoint and brutally beat Vinh’s father and uncle. Then they were towed back out to sea on a smaller boat with no working motor or fuel. They were left to die.

“[We] suffered the slow and painful degradation of basic human dignity … there was no food. No water. There were no toilets,” Vinh says.

With no hope in sight on the waves, his parents considered the unimaginable: throwing their children overboard rather than watching them die of starvation and dehydration.

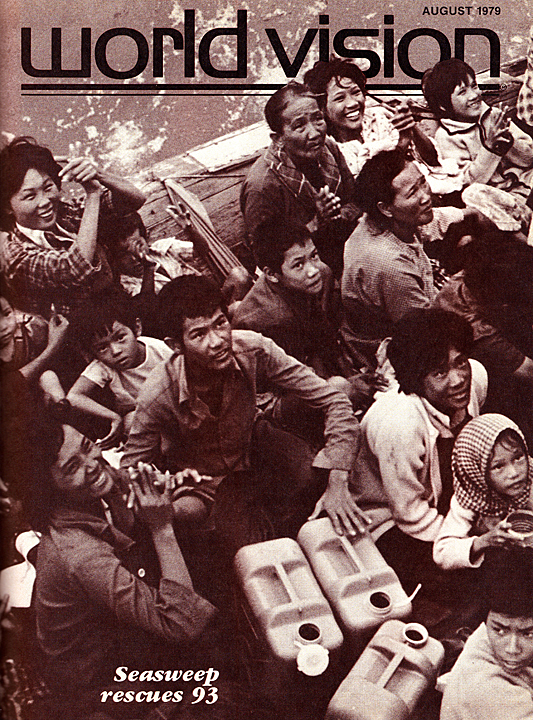

But on the sixth day adrift, the World Vision freighter Seasweep appeared on the horizon. Seasweep was the first international rescue ship to provide food and medical care to stranded refugees.

Seasweep took 93 people on board that day. In time, they were transported to a camp in Singapore. An Arkansas church eventually sponsored the Chung family and helped them to relocate to the United States.

When they landed in Fort Smith, Arkansas, Thanh, Vinh’s father — a successful businessman in Vietnam — found himself with no transferable skills.

“He didn’t know much, but he knew that he had eight children to feed,” Vinh says. So his father eventually found an assembly line job building air conditioning units for $7 an hour.

For more than three decades, he never missed a day and worked every overtime hour possible. In time, Vinh’s parents had three more children.

They were frugal, and generous friends, neighbors, and organizations helped keep the Chung family fed and clothed.

“Today I really don’t see how they [his parents] did it,” Vinh says. “The only way that I can really explain this as an educated man, a man of science, [is] God performed a miracle to provide for our family. Somehow at the end of the day we would have just enough.”

Despite starting over with nothing in the United States, things always seemed to tip in Vinh’s favor. He became an all-state football player, valedictorian of his high school class, and was college-bound — to Harvard.

His parents scrounged up enough money for a one-way bus ticket to Washington, D.C. From D.C., he arrived in Cambridge with two duffel bags and $20 in his wallet.

“I was dumped into deep water without knowing how to swim,” Vinh says. But he survived this elite setting through hard work and by the generosity of people around him.

Medical school, also at Harvard, was next, along with a Rotary Fellowship to study theology in Scotland, and a Fulbright Fellowship to research herbal medicine in Australia.

Today, Vinh has his own growing dermatology practice in Colorado Springs, Colorado.

Vinh is acutely aware that his life could have ended in the sea at age 4. He could be doing backbreaking assembly line work in the suffocating Arkansas summer like his father or living in a shack with no water or electricity like his cousins, whose boats floated back to Vietnam 32 years ago.

From one beach to another, the smell of the salt air connects Vinh to his past. It’s a stark reminder of where he’s come from that gives him clarity and a deep sense of gratefulness.

“So I take [this] as a reminder of what I do have, of how much we’re blessed with opportunities and the ability to move from being in a position of vulnerability — a position of powerlessness — into a position now where we can actually give to others,” he says.

Vinh sees himself as one to whom much has been given — a wife and family, an education, a profession, the opportunity to live freely and to raise his three children without fear. And of whom much is expected; so he sows back into the cycle of generosity that has allowed him to flourish.

“All the pieces of my past are always coming together and I feel God uses our experiences to further his Kingdom. We’re still trying to figure out how that is going to be. That’s the exciting part, we don’t know, but we know it can be something great.”

Comments