World Refugee Day remembers those who have been forcibly displaced from their homes. Their number is staggering: almost 60 million. Today, 1 in every 122 people is a refugee, internally displaced, or seeking asylum.

But these people are more than just numbers. They are some of the most incredible people on earth, as World Vision writer Kari Costanza found in Iraq.

I came home from Iraq feeling ashamed.

For more than two decades, I have traveled to 35 countries to report stories for World Vision.

I have met the best people on earth, from Obed Byamugisha, who each day puts his life on the line to fight child sacrifice in Uganda, to Margeret Alerotek, who telephoned Ugandan rebel leader Joseph Kony to urge him to stop fighting — an act of courage that may have cost her life.

Wherever I go, I find bravery and beauty — people who live and breathe the conditions described by theologian Frederick Buechner: “Here is the world. Beautiful and terrible things will happen. Don’t be afraid.”

I didn’t expect to find beauty or bravery in Iraq. I just expected to be afraid.

I’m embarrassed to say that until last month, I painted the people of Iraq with broad brushstrokes. In my mind, I dehumanized them.

I was so wrong.

What I found last month in northern Iraq was a group of people whose faith and love of beauty is far stronger than mine.

They are among the best people on earth. Let me introduce you.

Ibtihal, Huda, and May are artists.

In the summer of 2014, armed groups drove them from Mosul. They joined 3.4 million Iraqis who have had to flee their homes, often leaving everything behind — 120,000 of them Christians. These women now live with 5,500 others in a camp in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq.

A year ago, Ibtihal, Huda, and May started a small business — making mosaic tiles with a group of women from the camp.

The tiles depict the letter “N” for Nazara — the Arabic symbol for Jesus of Nazareth.

“They marked our houses with the letter N for Nazara,” says Ibtihal, speaking of the armed groups. “[The ‘N’] means these houses belonged to [them]. They stole our houses. Our furniture. Everything,” says Ibtihal.

May joined the group of women at the camp with her daughters Rita, 20, and Sally, 17. Being forced from her home wasn’t her first loss. May lost two brothers in a 2010 church bombing in Mosul. Four years later, she lost her home and her every possession.

Her acceptance of such tragedy is dumbfounding. “It is written that we will be displaced,” says May. “This is our faith.”

The women say the mosaic “N” symbolizes their unshakeable faith.

“[They] could destroy our church,” says May’s friend, Gaydaa, “but they can’t destroy the small church inside us.”

Ibrahim is a painter.

His family escaped from Mosul on August 6, 2014. Ibrahim had just built a beautiful home for his family. He had a good job with the government. His wife was a nurse, and his children were in school.

Overnight, they became homeless in their own country — internally displaced people unable to go home.

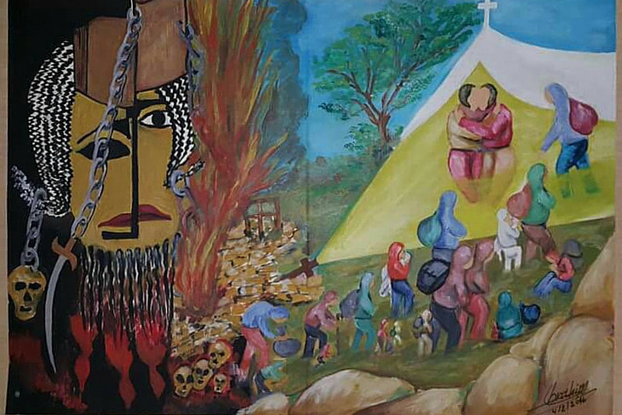

Ibrahim paints his feelings.

With beautiful colors and haunting imagery, he’s recreated the frightful night his family had to flee. In the reds and the blacks, you can feel the terror of that night. But there is hope: a cross amid the rubble, which leads to a place of “peace, brotherhood, and comfort,” he says. That’s where Ibrahim and his family live now in northern Iraq. It may be temporary. It may be longer. They don’t know.

Another painting shows a man lying in the street. Ibrahim says the man is disheartened and displaced, hoping to return home, but not knowing when.

He worked in blues to create a stormy sea. “Looking at the sea gives you mixed feelings of beauty and fear for the people who want to travel outside, seeking a better future,” he says.

But this sea is deadly. Ibrahim knew of two families from a nearby village who drowned like so many others, trying to escape.

Ibrahim has lost his home and his occupation but it cannot quash the creative spark in his soul.

“The Christian people in Iraq are creative,” he says. “They were artists — music and drama. If the Middle East loses its Christians, it will be a disaster.”

Ibrahim wants to stay in Iraq. He wants to continue to be salt and light in a troubled place.

Father Daniel is a Chaldean priest.

Old beyond his years, he turned 26 this week.

With another priest, Father Douglas, Father Daniel oversees a camp for more than 700 Iraqi Christians, most who fled their villages on August 6, 2014.

Father Daniel is faithful and funny. He loves McDonalds’ hamburgers and Britney Spears. Before becoming a priest, he studied to become a doctor with Muslim classmates in Ukraine. His classmates bombarded him with questions about his faith. To answer them thoughtfully and thoroughly, Daniel took online courses in theology. Through that study, he decided “to become a spiritual doctor instead of a regular doctor.”

Father Daniel knows every child in the camp — all 200 — by name. When he walks through the camp, they gravitate toward him, holding his hand, basking in his smile. He preaches in Aramaic, the language Jesus spoke. Father Daniel says when Jesus comes, he will be happy to translate for the rest of us. When I am with him, I feel there is no place I’d rather be on that glorious day.

World Vision works with Father Daniel to provide the internally displaced people with what they need — food vouchers to buy things they can’t otherwise buy: protein like meat and cheese, and supporting small businesses such as hairdressing, cooking, and tailoring, even a playground for kids who used to play outside in their villages. The children live in cramped quarters with no privacy. They need a place to play.

Father Daniel’s new congregation is hungry for healing. “What happened to them was a big trauma,” he says. “They need to be educated on how to deal with this loss. It’s really big. They worked for so many years. They have nothing.”

But they need more than just handouts, he says. They need hope.

“We are trying to [help] them [be] creative,” he says. “Iraqi Christians — when they are persecuted, they become creative.

“We opened a Child-Friendly Space,” says Father Daniel. “We did classes in music, flute, guitar, violin, dancing, drama, and drawing.”

When the children first came to the camp, Father Daniel had them draw their feelings. They drew guns and bombs and war.

“I hosted the same [drawing exercise] after six months,” he says “‘Now draw your dream,’ I said. I saw pictures of doctors, teachers, singers, and dancers — Britney Spears and Lady Gaga.”

Father Daniel loves Britney Spears.

I love Father Daniel.

World Vision is working through the church in Iraq in a powerful way providing food vouchers, child protection, programs for young people, and healthcare for people who have no access to basic medicine.

In the same region, World Vision also works with Yazidis and Muslims, providing them with food, shelter, child protection, and clean water.

We do incredible work serving incredible people.

I came home from Iraq feeling ashamed but inspired.

Would my faith be so strong under so much pressure?

Would I still write and take pictures?

Would I still appreciate beauty — in people, in music, in art, and in nature?

Would persecution pique my creativity?

I hope so.

When that day comes, I hope I can be like an Iraqi Christian, finding beauty and bravery, being my best — God’s best version of me — in the very worst of times.

This World Refugee Day, join us in responding to the urgent needs of refugees in Iraq and throughout the Middle East. Make a one-time or monthly donation.

Read more about the daily challenges that refugees face, living and raising their children while displaced from home.

Comments