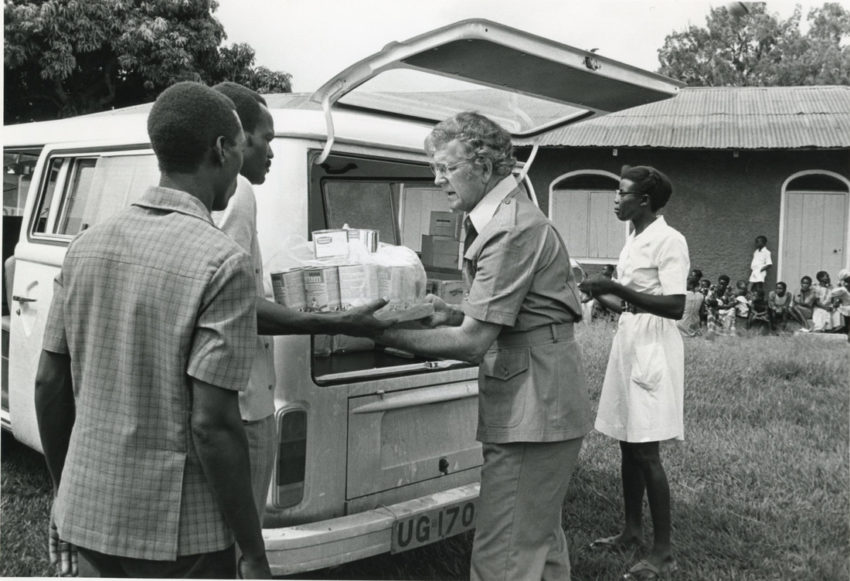

Thirty-five years ago, Ugandan dictator Idi Amin was overthrown after a brutal eight-year reign. His regime killed up to 500,000 people, persecuted Christians, and left Uganda a broken nation. In the aftermath of this genocide, World Vision worked with the African Evangelistic Enterprise and other partners to provide emergency supplies, and then-World Vision U.S. President Stan Mooneyham promised $500,000 for relief and reconstruction. This article about his visit to Uganda appeared in World Vision magazine’s July 1979 edition.

The pink L-shaped building high on Nakasero hill is in that part of Kampala familiar to all enemies of former Ugandan President Idi Amin. The three-story structure was once the work place for some 300 men and women. Most of those handpicked employees were not your run-of-the mill government civil servants.

The personnel in the pink building used high-performance electronic equipment to do much of their work. They gave scrupulous attention to detail. Their unquestioning loyalty to Amin set them apart. Until recently, they were Uganda’s elite.

Now, the windows of that innocent-looking office building are broken, rooms in disarray, and doors permanently unlocked. A Tanzanian soldier in his early 20s shuffles through its dark, empty corridors. Another soldier stands sentry in front of a door with a sign that reads: NO ENTRANCE — TOP SECRET.

Actually, it’s no longer a secret at all. The horrible truth is out: This place was once Idi Amin’s personal murder factory.

The official name was the State Research Bureau, the SRB. But the bureau had little to do with affairs of state, and the research was not of a university variety. Instead, it was the headquarters for Idi Amin’s dreaded secret police. Here, “enemies of the state” were brought for slaughter. Offices became torture chambers where crazed agents of Idi Amin strangled, shot, and beheaded their victims. Sometimes as many as 20 died during a single day.

‘God, please let me die quickly’

An Anglican pastor, the Reverend George Lukwiya, was one of the few survivors of this place. As we stood in Mr. Lukwiya’s former cell, he told me what it was like to be a victim of Amin’s wrath.

“One day,” he said, “the secret police picked me up, saying that I had made an attempt to assassinate President Amin. It was a ridiculous charge, but there was no convincing these people. So they brought me to the SRB. It didn’t take them long to strip me and start beating me. Many of my attackers were high on drugs and alcohol. Every time they tortured me, I thought it would all soon be over. They kept demanding a confession, but I had nothing to confess. So they just continued to beat me with the butts of their rifles.

“For three months I lived in constant fear. And quite often I’d pray, ‘God, please let me die quickly.’ At one time I found myself in a 10 foot by 16 foot room with 60 other prisoners. Every day, one of those men would either die or be murdered. Usually the guards would just leave the dead bodies there in the cell. Often we had corpses all around us for more than a week. The smell was horrible. We’d try to pile them up in a corner and cover them. Sometimes we’d all go for two weeks without water. Prisoners became so thirsty, they drank each other’s urine. We considered ourselves lucky if we got food twice a week.”

For more than three hours, Lukwiya spoke to me of the atrocities in that horrible place. He said it took the guards about 10 minutes to hammer a man to death. Women died more quickly because the guards simply cut their throats.

The more Lukwiya recalled the human horror he’d seen, the sicker I felt. It was a sickness mixed with anger and despair that begged the questions: How? Why? How could a madman rule his people with such terror and insanity? How could the world stand by so quietly and allow the genocide of these gentle people? While you and I slept in relative peace, Christian brothers like George Lukwiya languished in Amin’s chamber of horrors. But while he survived, 300,000 to half a million Ugandans throughout the country did not.

Eight long years of genocide

For eight long years, Idi Amin, self-proclaimed President-for-Life, slaughtered his countrymen. No one was safe from him. Everyone feared the knock on the door at midnight. On the outskirts of the southern Ugandan city of Masaka, one eyewitness told me that several nights each week, starting around 8:30 p.m., he would see Amin’s secret agents speed through his village in their Land Rovers and private automobiles. Within minutes, shots would ring out into the night. Sometimes he would sneak out to the clearing at the edge of the forest and watch. The killers would bind their victims with ropes, throw them to the ground, and shoot them. Others would be doused with gasoline and set afire. He said he could hear the screams for mercy — a mercy that never came.

One afternoon I took a walk through the tall grass of that execution ground. As I walked, I came across piles of human bones picked clean by vultures and bleached by the sun. There were ribs, leg bones, bits and pieces of clothing. And then, skulls. All a testimony to the eight years of Idi Amin’s reign of terror.

Statistics indicate that at least 60% of Ugandans are Christians. Another 6% are Muslims. Yet, it’s reported that Amin was ready to declare his nation a Muslim state. Christians — Catholics and Protestants — were at the top of the list for execution, especially two tribes, Lambi and Acholi. These groups are predominantly Christian, and they bore the brunt of Amin’s wrath.

Pastors and bishops of the Church of Uganda (Anglican) told me Amin’s spies would often sit quietly in church services. Days later, certain members of the congregation would simply disappear. Most were simply shot. Others were tortured. Some were fed to crocodiles. To be a Christian under Amin was to put your life on the line.

A deep pain that never goes away

It’s quite possible that every person in Uganda lost a loved one through sheer murder. Perhaps the most common greeting in Uganda nowadays is: “You still exist? That’s good!” It is good. But the memory of the number of fathers, mothers, sisters, and brothers will not go away.

Ever.

Never have I seen pain so deep. I saw it on the faces of small children still wondering why daddy never returned home. A grandmother choked back tears as she showed me her family album. Her 21-year-old son had been stuffed into the trunk of a car. She never saw him again. Her brother, recently married, was hammered to death. And as she told me these things, her grandchildren sat all around her. Their eyes were asking, “Why? How could this happen?”

That’s the question I kept asking. Yet, I guess I’m not surprised that a man like that could kill so wantonly. Amin is only the most recent headliner in a long list of tyrants who’ve played their treacherous roles in history. The brutality of Idi Amin is solid evidence that man’s basic condition is much the same as it has always been. Man’s heart is still deceitful and wicked, and still desperately in need of a Savior.

The brutality of Idi Amin is solid evidence that man’s basic condition is much the same as it has always been. Man’s heart is still deceitful and wicked, and still desperately in need of a Savior.

But try to explain that to a little girl who no longer has a father. Try to explain that to a boy who suffers from severe malnutrition because he hasn’t had decent food for months.

Children like these don’t need explanations. They need bread and milk. Their parents won’t profit from a political or theological analysis of the horror. Instead, they need a livelihood. Farmers who’ve seen no harvests for years need simple tools so they can once again work their fields. Factory managers need an infusion of new capital. An inflation rate of 300% a year needs to be brought under control. These are just some of the needs.

‘Relief, reconciliation, and reconstruction’

And at the heart of the reconstruction of the nation stands the church of Jesus Christ. Many of the old tribal chiefs have either lost their influence or have been killed. As a result, Ugandans are turning to their pastors and bishops for leadership. The message of the love of Jesus Christ is helping to pour oil on deep, deep wounds. Ugandan Christians are now free to share their faith openly, without fear of political reprisals. Hearts throughout the entire nation are open and receptive to the gospel. Once again, the suffering, martyred church has become the source of strength for a tortured nation.

When he stepped out of his plane at Entebbe airport, returning to his city after two years in exile, Bishop Festo Kivengere declared that Uganda now needs to concentrate “on the three R’s — relief, reconciliation, and reconstruction.” He said the church will do all it can to bring them about.

Later, at a press conference I attended at the State House, Yusufu K. Lule, then interim president, said he was also counting on Ugandan Christians to help restore the moral and psychological fiber of the nation.

Mr. Lule went on to say, “We have a generation of young people who have seen only the examples of violence, tyranny, murder, and disrespect for property. We must re-educate them with proper spiritual and moral values. It will not be an easy task, but we pray that we may do it in less than the eight years it took Amin to destroy our country.”

At that press conference, I promised the Ugandans that World Vision would contribute at least $500,000 toward the relief and reconstruction of their nation. Right now, World Vision is working through the Church of Uganda and African Enterprise to help provide food, medicine, and other emergency supplies. Each week, additional relief shipments enter Uganda from neighboring Kenya.

The struggle to rebuild is just beginning. I see in many a fear of revenge and reprisals against those who persecuted and killed. I see a stagnant economy that must get moving again. I see Ugandans young and old who are hungry, malnourished, and sick. I see tens of thousands of people who’ve forgotten how to trust, who now must somehow, in some way, attempt to regain a sense of their own personal dignity and pride.

A Ugandan proverb says: “The fruit you bear is what you will eat.” I hope the days ahead for Uganda will bring a rich, bountiful harvest of peace and reconciliation. May the fruit of that harvest remain sweet.

World Vision began its development programs in Uganda in 1980. Today, 35,600 children thrive with support from U.S. sponsors, and World Vision is improving millions of lives through water, sanitation, and hygiene; economic empowerment; health; education; child protection; and Christian discipleship.