Anniversaries: events deserving of reflection, reconnecting with memories. Some come with celebration, some produce perpetual grief. In the past few years, Margaret Ann and I celebrated our 70th birthdays and 47 years of marriage. It doesn’t get any better.

Others remember what was lost on Sept. 11 or recall how they felt when told of the premature passing of a loved one. In all cases, anniversaries draw us back to the critical events in our lives, unleashing memories while providing ongoing opportunities for reflection. What has changed? What is worth renewing? And, when events have been exceedingly painful, have there been any defining moments of redemption?

At World Vision, given its mission to a hurting and vulnerable world, most events have painful beginnings. Two that seared my conscience when I was president of World Vision U.S. are now being remembered as anniversary events: Romania, and the exposure of a country of warehoused children following the execution of President Nicolae Ceausescu in 1989; and Rwanda, 20 years after “the most efficient killing since Hiroshima and Nagasaki,” according to Philip Gourevitch, who wrote an account of the genocide.

These two horrific events will forever be a part of my memory. I cannot dislodge the visual impact of being in the midst of what had to qualify as man’s greatest inhumanity to man. World Vision colleagues, for example, may remember how difficult it was to talk about the thousands of dead bodies that clogged the rivers and streams of Rwanda. The emotions were simply overwhelming.

Two years ago, I was sharing the horrors of Rwanda with a group of Army chaplains. Eighteen years had passed since I stood on a bridge over the Kagera River in eastern Rwanda, transfixed by the palpable evil unfolding beneath me. As I recalled that moment, I began to cry. The emotions were still too strong to hide, impossible to contain.

Suffice it to say, we are marking two anniversaries that still haunt me. I will take them to my grave.

In Romania, a morally bankrupt government and a decrepit medical system went hand in hand. Children were the first to feel the effects. When medical attention could not heal a child’s problems — from bedwetting to autism — they were sent to a “home for the unrecoverables.” The words continue to reek of hopelessness and condemnation.

Following my first visit to such an institution in 1990, I penned the following:

The chatter of the children was constant, and the stench of urine filled every room, mattress, and rag of clothing. Flies were ubiquitous. Filth covered everything. But it was the visual images we couldn’t escape. Ten little boys huddled in a corner of the same bed and fought for the same blanket. No one could exist alone — not the autistic children, nor the Down syndrome children, nor the crippled children. Some rocked quietly, while others engaged in more violent self-stimulation.

We were advised to “hold on to their smiles.”

Smiles dominated broken faces, twisted bodies, and undeveloped minds. Irrepressible smiles provided the only façade to the gloom of our environment.

It gets worse. Once a child became too sick to live, their names were taken off their cribs, and they were placed down into a windowless cellar. There, their lives would end, alone.

Burial was not always assured. In the summer months, when the ground was soft, a grave would be dug. Once the ground froze in winter, however, the lifeless child was simply laid on the surface, susceptible to marauding dogs and the final indignity for Romania’s discarded youth.

In the genocide that was Rwanda in 1994, there were too many human corpses to bury. Weapons had been stockpiled, lists of Tutsis and moderate Hutus had been compiled, gangs of radical Hutu youths — the Interhamwe — had been trained to kill. They were effective. In less than 90 days, 800,000 Rwandans would die. For many, their final resting place would be a nearby river or stream. Again, my thoughts, written in the summer of 1994:

Grotesquely bloated bodies floated down the river, silent testimonies to a world yielding to sin, a world increasingly incapable of dealing with humanity’s deepest differences. We stood transfixed.

Anniversaries of these horrific events need a redemptive moment. As the bodies collided beneath the bridge, a mist from the river began to ascend, ultimately challenging a brilliant African sun, producing a massive rainbow. The rainbow became my focus.

For me, as well as for Noah millennia before, the rainbow was a reminder that God was still in charge. Even at points of deepest suffering and seemingly total destruction, God is in control. He is a promise-keeping God, one promise being that his grace is more abounding than any and all of our sin.

Whenever the rainbow appears in the clouds, I will see it and remember the everlasting covenant …—Genesis 9:16

Similarly, Romania also experienced a redemptive moment. In late 1991, an ecumenical gathering took place around an indigent cemetery — the same cemetery that loosely held the final remains of that human way station known as a “home for the unrecoverables.” All of the great theological traditions of Eastern Europe had chosen this place to gather.

The service began. The pathos of the moment produced a common pain. Tears were shed and hearts were broken. Most importantly, ethnic differences gave way to a Christ-centered love. Scripture was read, followed by Holy Communion. Another premature death and a body broken were remembered, making the ground holy. Legitimate hope for a better future became a reality.

Hope is the anticipation that tomorrow’s reality will be better than today’s. This expectation, however, is made more credible if there is something tangible in the present that helps to authenticate that hope. The rainbow was tangible. Holy Communion is equally tangible. Both were designed to help us remember and to celebrate anniversaries.

Scripture tells us that we “do not grieve like the rest of mankind, who have no hope.” We have anniversaries. They anchor our past experiences and relationships. And, like the empty tomb, they justify our hopes and dreams for the future.

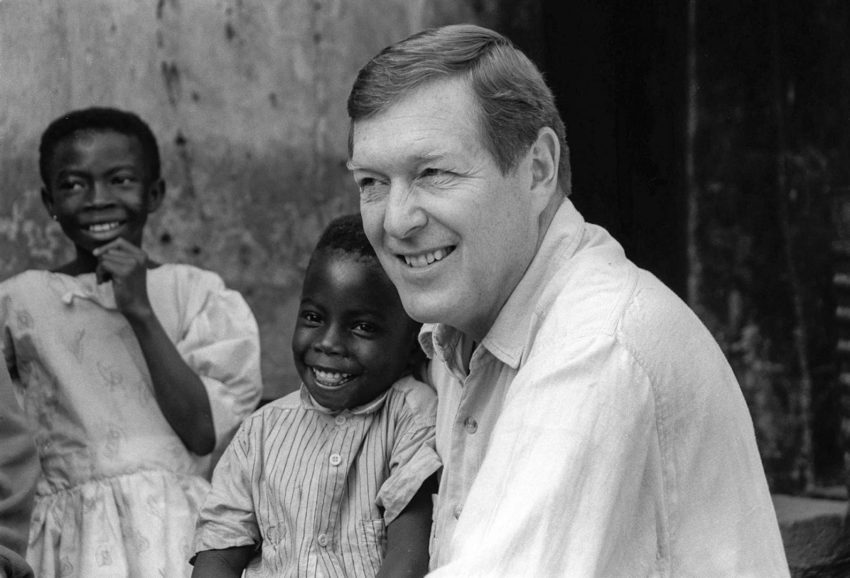

Bob Seiple was World Vision’s U.S. president from 1987 to 1998. He later served as the U.S. State Department’s first ambassador-at-large for international religious freedom. Following government service, he and his wife, Margaret Ann, founded the Institute for Global Engagement, a think-and-do-tank working with persecuted people of faith in the world’s most difficult places.