This month — and every month — Bikeledi Emily Mphahlele, 43, walks an hour on dirt roads and through fields strewn with cow dung and garbage to reach the nearest community health clinic.

She makes her way down a dark hallway with others staring at her, a gauntlet of embarrassment Emily must endure before she finally arrives at the building for HIV patients, which is separated from other patients.

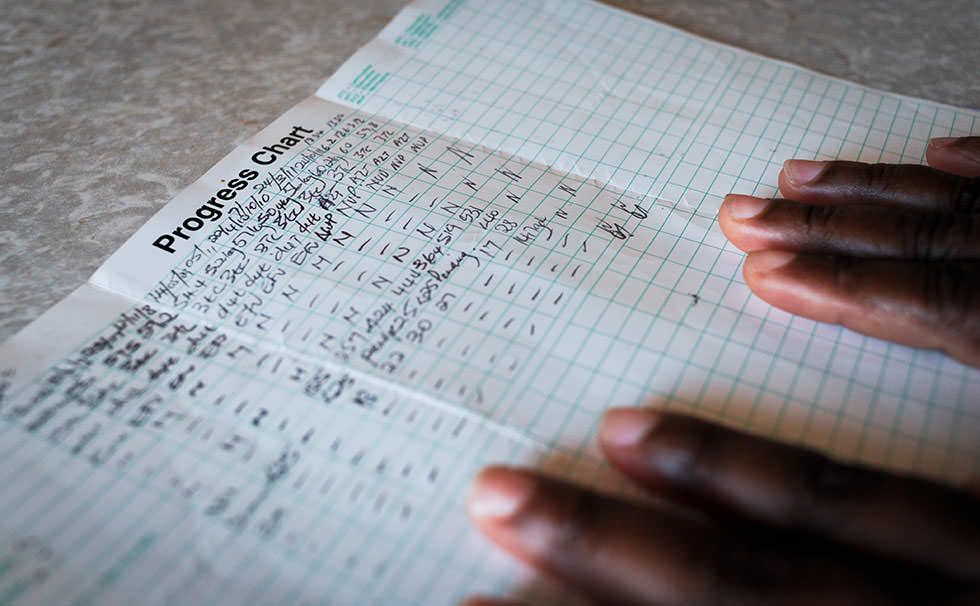

She waits — sometimes several hours — to spend a few fleeting minutes with a physician. The doctor reviews Emily’s latest test results, asks a couple of questions, and hands her a small piece of paper that represents the distinction between life and death. As she leaves, she clutches this prescription for her next government-funded monthly regimen of anti-retroviral medications (ARVs).

Like thousands of other women in Botshabelo, a sprawling township of 210,000 black South Africans, Emily is living with HIV, the virus that causes AIDS. Diagnosed in 2009, she began taking ARVs in early 2010.

Unlike many in Botshabelo, Emily is open and candid about her HIV status. Her transparency is rooted in the belief that she can help others overcome the relentless stigma still associated with AIDS. But it comes with a price.

“I am sometimes afraid of my husband,” she says, tears forming at the edges of her eyes. “He has told his sister, ‘I will kill her, and I will kill myself.’ I have been sleeping alone for six years since HIV. I have not gone outside our marriage.”

Emily is one of more than 5.6 million South Africans infected with HIV, compared to 1.2 million Americans. Nearly 1,100 South Africans will contract HIV today, and tomorrow, and the next day. More than 314,000 die every year, according to UNAIDS.

In contrast, in countries such as Uganda, HIV infection rates — while still devastating — have stabilized due to strong government leadership and timely public health campaigns.

Some contend AIDS persists in South Africa largely because many don’t understand the pandemic and deny its pervasive presence. Many attribute the nation’s culture of denial to former South African President Thabo Mbeki, who publicly questioned the link between HIV and AIDS during his time in office from 1999 to 2008. The president’s views slowed the public health response to rising HIV infection rates and perpetuated the social stigma against testing.

Such denial is evident in Botshabelo, especially among men today.

“The problem is men are secretive,” says Teboho Motseki, a counselor and chair of the Men’s Forum, a community-based group seeking to educate and enlighten local men. “They do not want to reveal themselves; they do not want to be open about their status.”

World Vision has worked in South Africa since 1967 and today provides a wide range of services to people affected by HIV. That work includes assisting Teboho in reaching out to local men, encouraging them to participate in the forum. In many rural South African communities, the stigma of HIV remains strong, a prejudicial stain on a person’s life and a persistent strain on relationships.

“If a man here is HIV-positive, he is ashamed,” says Teboho. “He does not want to talk about it with his wife or partners. In fact, men do not want to be blamed for infecting their partners. They insist ‘It is you who came up with HIV,’ even though most of the transmissions here are from men.

Sarah Masondo* knows the realities of living with HIV in South Africa. The single mother is certain her boyfriend of more than 12 years infected her with HIV. A petite woman wearing a stylish wool cap and jeans, Sarah looks a decade younger than her 32 years. Even while her 3-year-old son is down the street at preschool, she speaks cautiously about her life, livelihood, and living with HIV.

Sarah’s reluctance is rooted in fear of the prejudice she likely would encounter from her community.

“I thought it was the end when I learned I was HIV-positive,” says Sarah. “But some people told me, ‘It is not the end.’ And now I see. It is not the end of the world.”

Initially, Sarah was worried her son was infected, but she has since found out he is not. Her son’s father calls from time to time to make sure the child has food, Sarah says, but he rarely sees or speaks with the boy. Her former boyfriend also insists he doesn’t have HIV. “He told me ‘That thing [HIV] is yours,’” she says.

The father’s attitude reflects the denial Teboho deals with every day among the men he counsels.

Living with HIV, as Sarah and Emily will attest, takes diligence, persistence, and courage. When World Vision organized a women’s catering cooperative, both women joined. The women have learned to cook lunch for 500, host elegant dinner parties, and more. World Vision’s micro-lending and education programs make this and many other local businesses possible.

Martha Gwabeni, a World Vision volunteer who trained the women, personifies compassion. She conducts home visits, checking on the physical and emotional well-being of children and caregivers. Using money she earns from catering, Martha also purchases school uniforms for children whose parents can’t afford them.

Emily and Martha practiced their craft one afternoon in Martha’s covered patio. Amid a flurry of whisks, wooden spoons, and paring knives, the two women sliced, diced, and chopped lettuce, cheese, fruit, and vegetables. A closet nearby is packed with glass and ceramic bowls, tablecloths, china, shining serving trays, and elaborate centerpieces. After 20 minutes, they proudly announce their culinary creations: fruit compote and a mixed green salad with almonds and other garnishes.

* Name changed to protect identity

On Sunday mornings, Emily and many living in Botshabelo attend church, often learning about opportunities to serve their neighbors. The congregation of Grace of God Ministries, 60 to 70 people, gathers in a wooden building with a corrugated tin roof. Tarps and blankets cover the dirt floor. As prayers and worship songs erupt spontaneously, the sounds of the 90-minute celebration echo through the surrounding unpaved streets.

“A priest is not a priest because of what he does in front of the congregation,” Bishop M.R.J. Lephatsoe tells the gathering, “he is a priest because of what he does outside the church.”

The bishop, visiting from a church a few miles away, urges the congregation to “please God and serve the community… Look for the woman in need, the child who does not have food.” He speaks in a melodic, rhyming style punctuated by members shouting, “Amen!”

Like nearly 40 other local churches, Grace of God Ministries works with World Vision in Congregational Hope Action Teams (CHAT) to care for people on both ends of the AIDS spectrum: the terminally ill, and orphans and vulnerable children. CHAT, which is replicated in World Vision programs in many sub-Saharan nations, includes training boys and girls in life skills and preventing HIV infection. The program also hosts sports competitions at local high schools. CHAT is just one of many church-based interventions World Vision facilitates to provide training, educational materials, support, and encouragement.

The encouragement is foundational to Emily’s courage, especially as she endures the long treks to the hospital and frustrating delays waiting to see a physician. Once again, her determination and perseverance pay off. As she leaves the HIV clinic and walks down that dark hallway, she holds her head high. She ignores those staring at her. Grasping the prescription for ARVs, Emily dignifies the victory of pride over prejudice.

— Dean R. Owen is senior advisor for corporate communications for World Vision International.