Crying for Their Country

About 5,000 Syrians a day flee their homeland's bloodshed, a civil war now entering its third year. They escape the conflict only to find themselves living in squalid quarters in neighboring nations, in what the United Nations calls the world's worst humanitarian disaster of our time.

Many of the 1 million refugee children arrive in Jordan, Lebanon, and Turkey with nothing more than the clothes on their backs and memories of friends and home.

Each has a story.

By Sevil Omer | Photos by Jon Warren

Once, Israa thought her life mattered. On the day of Israa’s final exam, warring factions destroyed her school in Syria, shattering her way of life and goals of earning a high school diploma. “I was in school when the bombs hit,” the 18-year-old says. “The windows were blown out, glass everywhere and some hit my friends in the face and hands. Glass hit my face.” Israa dreamed of becoming a lawyer. She wanted to help women and children, protect them from injustice. "With war, there is no more," she says.

Thousands of Syrian schools have been attacked or destroyed in the country’s civil war. The honor student now spends her time confined to a tiny flat with at least 10 others in the most impoverished street in Zarqa, Jordan, near the Syrian border. She longs for the day when she can return home and run through her cobbled streets to hug her father, her teachers and her friends. “I want to return to Syria, my Syria, a free Syria.”

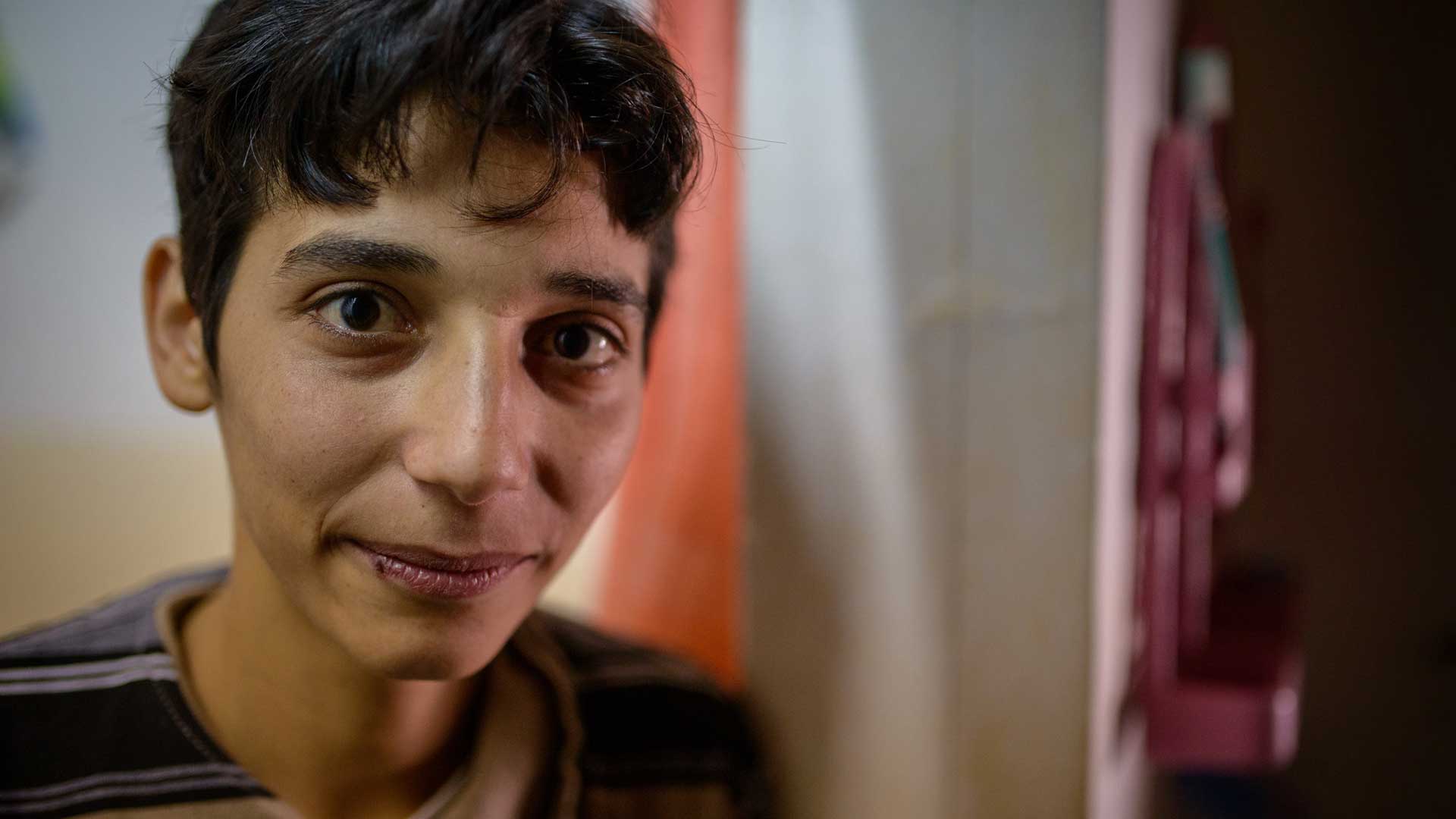

Mahmoud’s tough life has gotten a lot tougher. The 19-year-old Syrian refugee supports up to 10 members of his family now living in an abandoned building in Irbid, Jordan. He’s out on the dusty streets of the city day and night looking for work so he can eek out enough money to pay for bread for his sibling with special needs, his aunt, cousins, and young nieces and nephews. He earns about $5 to $8 a day — just enough to pay for clean water.

Through conversations, Mahmoud reveals his gentle demeanor. However, there’s a harsher reality behind his brown eyes and ready smile. “There is so much I have seen, so much death and so many dead people on the streets of my home,” Mahmoud says. His father and older brother were tortured and killed in Syria. Mahmoud fled Syria with hundreds of other men to the border of Jordan.

He was reunited with his mother and aunt at Za’atari Refugee Camp. He still speaks of school and how he hopes to return to the classroom so he can study.

Until then, he must be the father figure for his slain brother’s children, Hind, 4, and Mahoud, 3. The children rarely leave their uncle’s side and Mahmoud is torn each time he has to leave. Before he can cope with his ordeal, Mahmoud must now chase a living for his family’s survival.

Refugees like Nura who are living in urban neighborhoods in Jordan face rejection and discrimination. They feel trapped and are left to survive on their own in poor neighborhoods, with no sanitation, electricity, or clean water. The sound of Nura’s voice flows melodically like a fresh spring as she speaks of her peaceful existence in Syria before war. Her tone quickens when she recalls the bombs, bullets, and screams of her children during clashes between armed groups less than a year ago.

“We were sitting down for our holiday meal and I heard the noise, one that I have never heard before, a whooshing, a howl, a whistle. Then, everything I ever knew and had — all of it was gone,” she says.

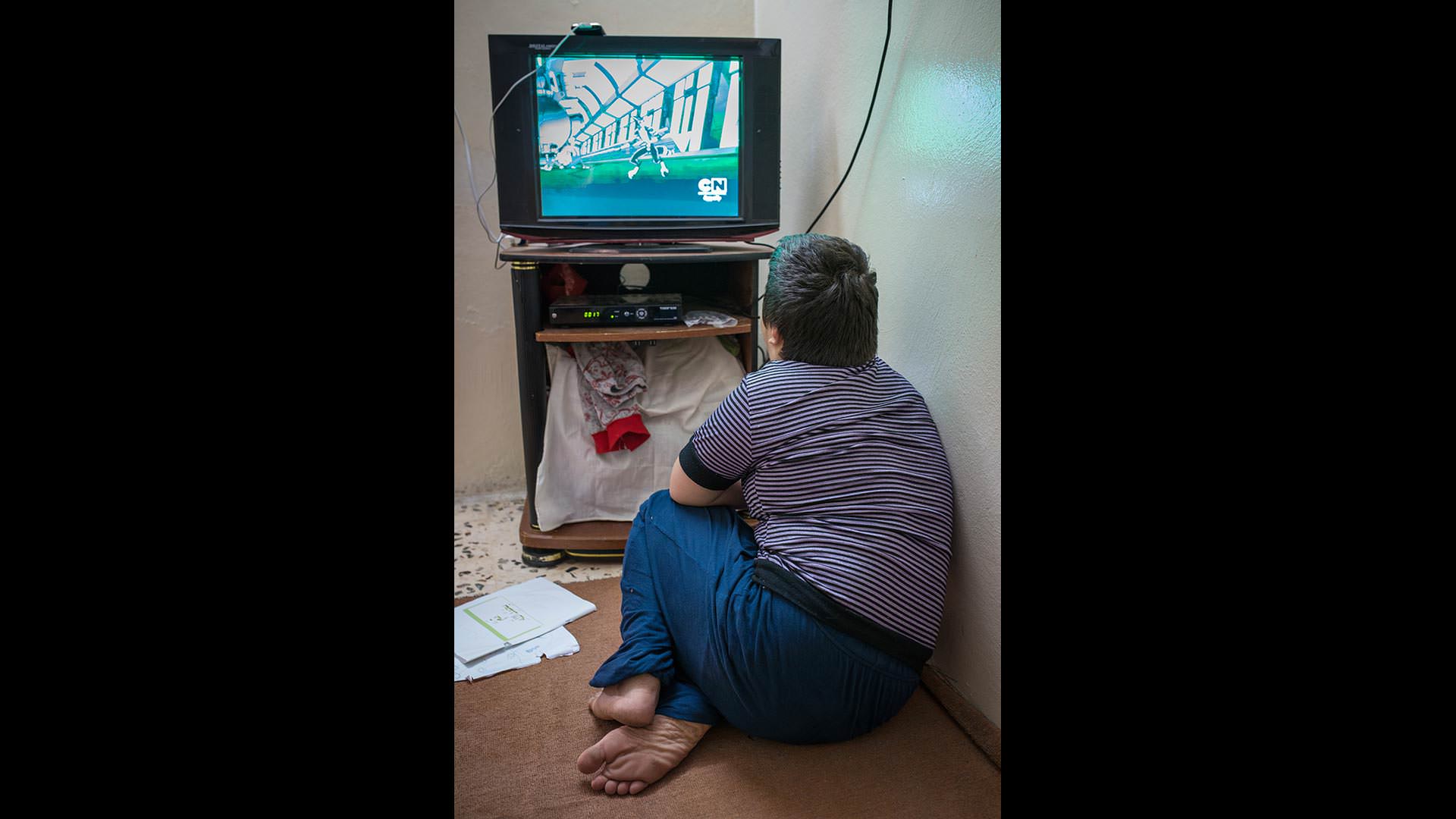

Ahmed and his wife, Amani, have four boys: Mohammed, 13; Yasen, 10; Shiekh, 7; and Ala’a, 4. “We fled because of my boys,” said Ahmed, who is a Syrian refugee living in Irbid, Jordan. “We left our home, my work, and our country because of our sons. We feared for the safety of our sons. There was so much fighting.” War has lasting effects.

The Jordanian government has opened public schools in the country to Syrian refugees, but the demand is great and the schools fill fast. Ahmed’s boys have not been able to attend school for two years and still are unable to enroll. The father fears his children have missed too much time to be able to keep up. The boys pass the time by playing with donated toys, including a plastic toy gun. It is the boys’ favorite plaything. Their favorite game is simulating scenes from battle and when not playing war games, they fight, their mother says.