World Vision’s award-winning photographers travel around the world every year, capturing moments of God’s grace and faithfulness as we follow Jesus’ example to show unconditional love to the poor and oppressed. They bring back stories that inspire us to action and compassion.

Discover what’s it like behind the scenes during some of these moments.

Gandhi, despair, and return to the brothel in Bangladesh

Written and photographed by World Vision photographer Jon Warren

* * *

The Bangladesh brothel was still there when Kari Costanza and I returned a year later, busy as ever.

Worse, one of the brothel women who told us last time how badly she wanted to get out was now even more deeply mired in the trade and resigned to her fate. Several others seemed to have disappeared completely.

A Bangladeshi reporter told us scores of children, both girls and boys, are still trafficked each day across the porous border with India.

It should have been a depressing visit. The problems haven’t gone away. I should have felt despair.

We were accompanied this time by World Vision U.S. President Rich Stearns, his wife, Reneé, and a group of dedicated, loving World Vision supporters. It’s virtually impossible to do good photography when you’re with a large group of people, particularly when many of them also have cameras. Chaotic crowds, short visits, and a rigid schedule are not a good recipe for the quiet, intimate real-life settings I prefer. But the folks I was with have powerful voices — and the chance to make a small contribution to their efforts was too important to miss.

I decided to work mostly with a 24-120mm all-purpose lens and a bounce flash to compensate for the slower lens opening. By the end of the trip, I had gone back to my standard kit of 17-35mm, 35mm or 50mm fast lens, and 70-200mm. So much for becoming more nimble.

One of our first visits was to a brothel community perched on a muddy dike in a large river. Smack dab in the middle of a line of rickety “working” shacks was a gleaming blue Child-Friendly Space crammed full of children eager to learn and play. We asked children what they dreamed of becoming when they were adults. They answered: doctor, teacher, driver, World Vision staff! Not one of them said sex worker, even though they are surrounded by the trade day and night.

We met with Rusmi (not her real name) and her parents. She was kidnapped by a trusted teacher and made into a sex slave at 12. Her father, ignoring the counsel of neighbors to abandon hope, spent every last taka the family had to find her. World Vision not only helped track her down and convict her abductor to a 30-year prison sentence but also worked with their neighbors and school to make sure she was welcomed home.

I had only a few moments to photograph the family without showing their faces. So I photographed them from behind — shallow depth-of-field against a dark bamboo stand to emphasize Rusmi’s delicate long hair, her mother’s supportive touch, and the upright father, who his wife said “wept like a woman” when he thought his daughter was lost.

Contrast this with vibrant Child Forums we visited, full of articulate, passionate teenagers (many of them sponsored through World Vision). In the Child Forums, they spread the word about trafficking dangers, promote responsible parenting, and planning for a productive future.

A little girl at one of the Child-Friendly Spaces grabbed all our hearts. Her name, Sonali, means “golden” in Bengali. Her mother, a prostitute since age 10, invited the women in our group to see her place of business across the street. It was a moment I needed to capture. When the women gathered around her and laid hands on her in prayer, everyone was in tears. No one wants Sonali to end up in the brothel.

More than a catalog, Kenya

Written and photographed by World Vision photographer Lindsey Minerva

Canon EOS 5D Mark II

70-200mm lens, 1/250th at f/7.1, 250 ISO

* * *

This photo was taken in only 1/320th of a second. But for me, it was years in the making.

Almost 10 years ago, I was freshly graduated from high school and enrolled in beauty school in my hometown. Really, I was floating directionless, killing time while I figured out what to do with my life.

Christmas rolled around and the usual barrage of catalogs came with it. As I sorted the mail, I picked up the World Vision Gift Catalog and flipped through the pages. It was filled with farm animals, tools, and medical interventions. Then my eyes landed on a photo of a child and a mosquito net.

At the time, a mosquito net hung above my bed, because it was fashionable in home decor. I didn’t understand its practical application. The product description in the catalog explained that every 30 seconds a child dies of malaria, and a simple bed net could help prevent children from contracting this disease as they slept.

An image of the preschoolers my sister taught flashed through my mind. If she had 30 children in her class, there wouldn’t be any survivors after 15 minutes of recess. I couldn’t wrap my mind around that reality. I was stunned, angry, and sad. I was mad that it was happening, mad that I didn’t know, and mad that the world was letting it happen.

Suddenly, time wasn’t something to be wasted, but a precious commodity I had been given. I had a life, and I wanted to spend it helping other people live. The things I was doing — my entry-level corporate job and beauty school — didn’t fit with my newfound perspective. I wanted my daily work to be about giving people a window into someone else’s experience and inviting them to become part of the story.

My focus quickly turned to storytelling. I finished beauty school but traded in my makeup brushes and tweezers for a camera, notebook, and pen. I dove into college and journalism classes as major newspapers across the country were closing their doors. I had no idea what the future would hold, but I knew I was exactly where I was supposed to be.

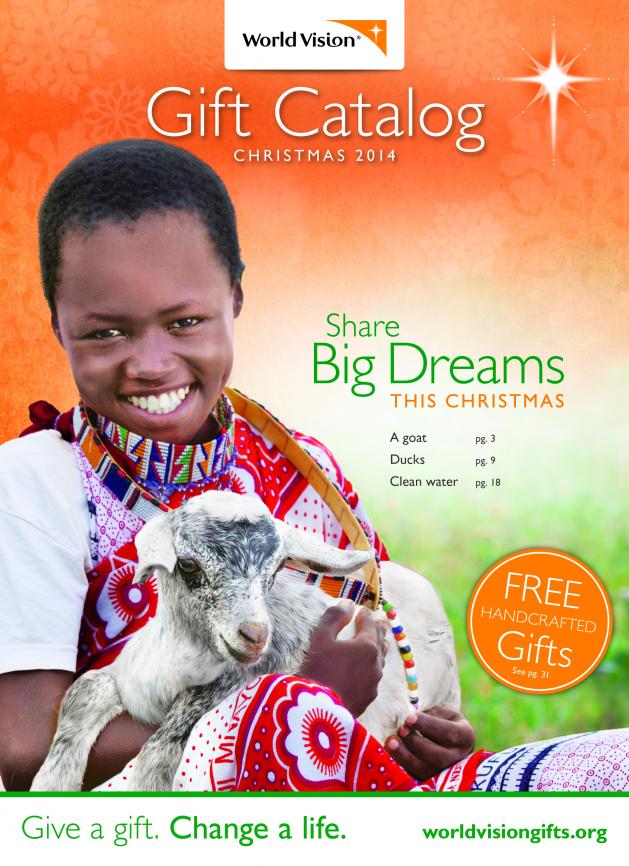

Recently as I sorted through my mail, Benson, who I met and photographed in Kenya earlier this year, smiled back at me from World Vision’s Gift Catalog cover. Tears filled my eyes. What God made possible was more than I could have asked or imagined. “This is real life,” I told myself as I flipped through its pages. Simeon, Benson’s little brother, is in the pages of the catalog holding a chicken. Lucy, his little sister, is a few pages away holding a goat.

I thought back to the day I spent with their family. Benson, Lucy, and Simeon started out shy but quickly warmed up to our team of local World Vision staff and visitors from the U.S. office. The whole team pitched in to make photos happen: holding reflectors, handling animals, translating, playing games as one child was photographed and the others waited. I wouldn’t have a single frame without them.

The crew was patient and flexible as the light changed and goats decided they no longer cared to be photographed. There was talking, laughing, tea-drinking, and lots of photos.

I loved watching the children interact with their father, a kind and gentle man. They crawled in his lap and put their arms around his shoulders as I sat and talked with him. He was so proud when I showed him the photos of his family.

Ten years ago, I had no idea what God was going to do when I first picked up the Gift Catalog. But he did. The number of children dying of malaria has been nearly cut in half — from one every 30 seconds to one almost every minute. While one child per minute is still too many, the progress makes my heart resonate with hope. Change is more than a possibility. It’s a reality.

Not so long ago, I hadn’t heard of malaria or spent much time outside of my hometown. Today, I have the incredible privilege of using words and pictures to bring help to children around the world. When I think about what God has done, I’m filled with awe, gratitude, and humility.

The brokenness of our world will always give us reason to despair, but when we enter the suffering of others and allow it to change us, we get to be a part of the redemption story God is writing.