Dreams flow freely: Loveness and the gift of water

Story by Laura Reinhardt / Photos by Amy Van Drunen

Loveness dreams of becoming a doctor, but for a long time that dream felt out of reach.

That’s because, as the eldest of four children living with their grandmother in Zambia, Loveness, at age 14, was responsible for collecting daily water for the family — an incredibly time-consuming task. Women and girls like her across the developing world spend a collective 200 million hours every day gathering water.

Loveness struggled in her studies because she spent up to six hours each day walking to the nearest well for water. Sometimes the task took even longer because the shallow well would often run dry. When that happened, she would have to sit and wait until the well filled up again.

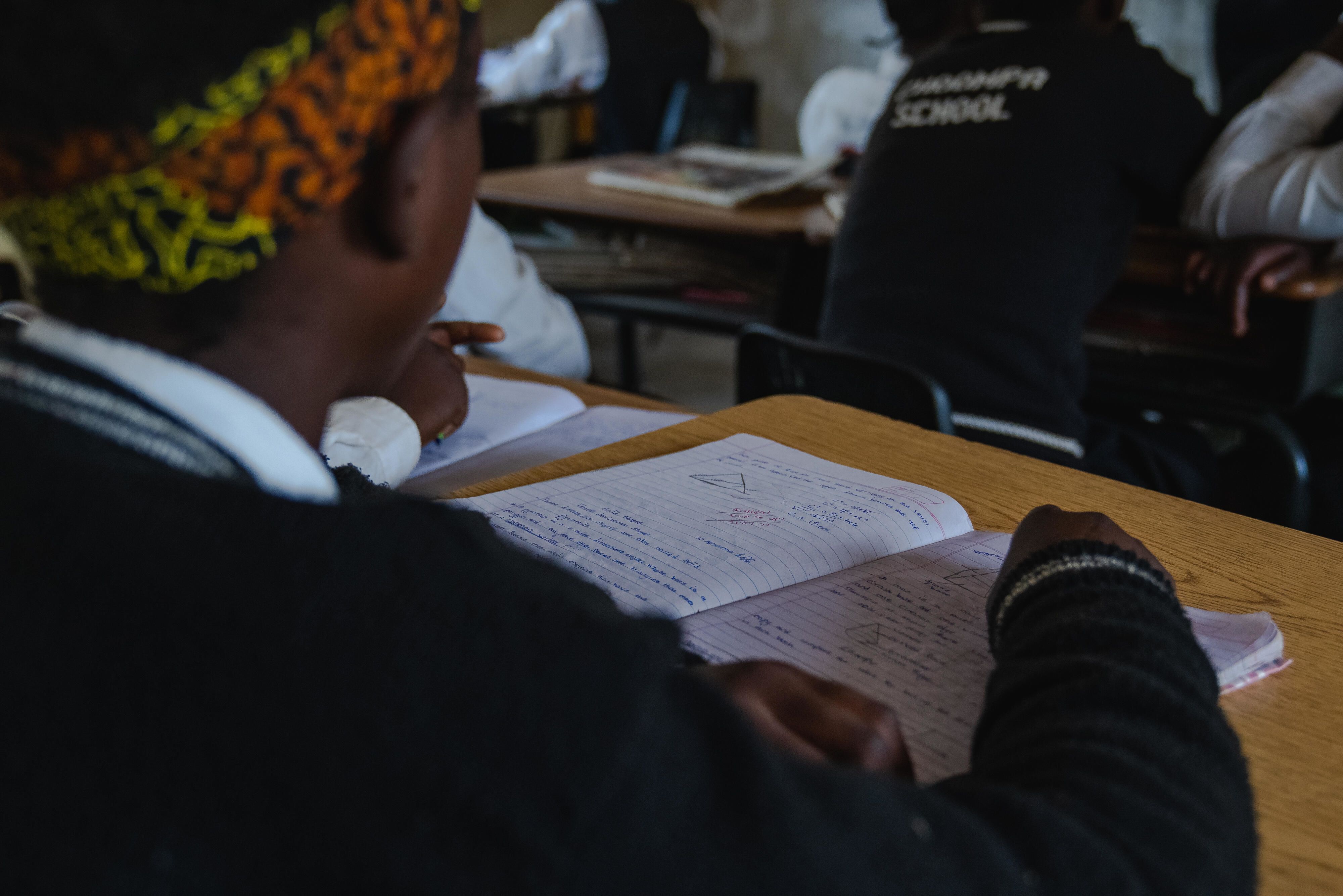

“I had no time to study. Most of the time for studying was spent getting water,” she says. Not only did she not have time for homework, but the morning walk for water regularly made her tardy to class.

“When I [would] come late for school, I would find my friends had already learned something,” says Loveness. “I would miss the whole first lesson.”

There are no make-up lessons at Loveness’s school, which is typical in rural Zambia. And that left Loveness falling further and further behind.

Dangers on the walk to water

Carrying a heavy water bucket on your head for long distances, as women and girls like Loveness do, exacts a toll on the body. “It was too heavy for me,” says Loveness. “My neck was burning.”

And then there were the dangers she faced on the way to the well. She regularly started off for her first water gathering of the day at 3 or 4 a.m., long before sunrise.

“It was so scary. Sometimes we’d hear a lot of sounds in the dark,” Loveness says. “I was afraid of wild animals.” She also feared men who might lurk in the darkness waiting to assault a solitary girl as she walked. Ngandu, a local teacher, says that many of the teen pregnancies in the village during that time could be attributed to the vulnerability girls faced as they gathered water in the dark hours.

Absenteeism and bullying

Ngandu explains that tardiness and absenteeism were common due to the lack of clean water access. Girls and boys alike suffered from illnesses due to dirty water — and the teachers did too because they drank the same water as their students.

But teen girls like Loveness often missed school for another reason: up to five days a month during their periods, they had to stay home because the school lacked facilities to accommodate their needs. As Ngandu explains, “Schools that have only pit latrines see a lot of absenteeism when girls have their periods.” Plus, boys at the school would taunt menstruating girls with comments like “You are losing your blood. This blood makes you dirty.” Understandably, this discouraged girls’ attendance even further.

These combined factors contributed to Loveness’s failing grades. And her personal dream — of one day becoming a doctor — was in danger of disappearing.

Community-wide change

Seeing the challenges faced by students, like Loveness, in 2017 World Vision worked with the members in her community to drill a borehole and establish water access for Loveness’s school and the surrounding area.

Clean water access has made a huge difference for not just girls but all the community’s children, who can now count on having access to clean drinking water at school. As Ngandu says, “They concentrate. They have no worries that when they go home [at lunch], they have to get water.”

There’s also less absenteeism, as children are rarely ill with waterborne sicknesses like diarrhea. Because students are no longer missing class, grades across the school have improved.

This is due in part to World Vision’s introduction of a WASH (water, sanitation, and hygiene) club at the school, which Ngandu leads and Loveness participates in.

Club members meet every week for two hours for lessons about safe sanitation and hygiene, and together they decide on ways to share what they’ve learned with other students and their own families. Loveness’s favorite lessons are about menstrual hygiene and general sanitation.

From taunting to advocating

As a result of this training, the boys in the community have made a remarkable shift in their attitudes toward the girls. Ngandu has even included the boys in the process of making homemade sanitary pads for the girls’ menstrual cycles.

They’ve gone so far as to become advocates for the girls’ needs. Ngandu says that if the boys notice a girl has started her period during class, they’ll say, “Hey, let’s go outside to give a chance for the girl to prepare herself.” Loveness says about the change she sees in the boys, “They understand. They no longer laugh at us. We feel free to mingle.”

Another thing Loveness feels free to do now is learn. Part of that freedom comes from the sanitation and hygiene facilities that World Vision built at the school in 2020. They include flushable toilets — seven for the girls and five for the boys. Two of those are wheelchair accessible, indicative of the strides the community is making toward equal access and opportunities for all people.

“This time around, the girls are very assertive. They’re able to stand for their rights,” Ngandu says of the positive changes that the new facilities have helped bring about. “That system of staying at home for five days is no longer.”

From lack to plenty

Access to water also impacted the lives of Loveness’s entire family.

Her grandmother, Valleria, belongs to a club that weaves baskets from sticks and dried grasses. In the past, she had only a small amount of time to make the baskets and sell them at a local market. The rest of her time was spent collecting water.

But with water access nearby, she can now spend more time weaving the baskets and thus earn more income for the family.

The family is also better able to care for their livestock. Before they gained reliable access to water, most of their animals died during the dry season. They could sustain only one pig and three goats. Now they’re tending eight pigs, six piglets, five goats, and 15 chickens.

“We have ample time now” for the activities that help the family thrive, says Valleria.

Loveness is experiencing the benefits of that abundance in her studies, too. “I now have enough time to study. I no longer [come] late for school,” she says. “Because we get clean water, then we come every day because we are not getting sick … What we learn in WASH club, it [helps us] come to school regularly and improves my grades in the end.” She’s gone from failing grades to achieving marks of 85% to 95%.

She’s even able to play games with her siblings and friends. That’s something that she rarely had time to do before.

Valleria sees a change since Loveness joined the club. “Before, Loveness used to have to be asked to clean the dishes and sweep around the compound. Now she does these chores before she’s even asked.” That’s because she knows the importance of sanitation and hygiene in keeping her whole family healthy and strong.

Loveness’s dream of saving lives as a doctor feels within reach now. She says that having clean water and the knowledge from the WASH club will help her to achieve her goal.

Imagine all the lives she will touch in that profession. There’s no telling what the people she might save will go on to accomplish. Because of access to clean water, she now has the opportunity to work toward her career dreams — and to create an impact in her community well into the future.

Give dreams a chance to come true through the gift of clean water.

Story published on March 19, 2024