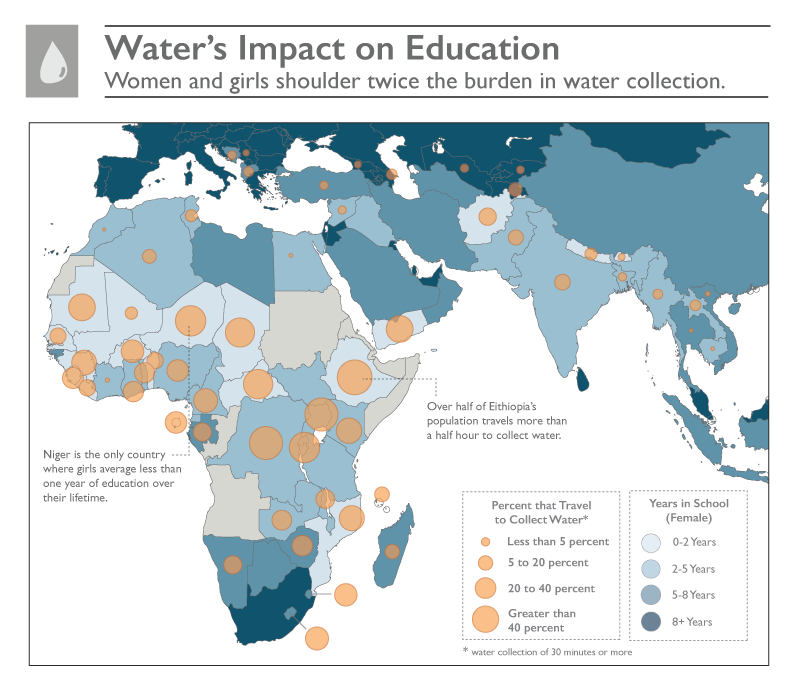

Gender inequality starts at an early age. It sits on the shoulders of young women in sub-Saharan Africa, where it can take more than an hour just to get drinking water, where in over two-thirds of households* women are responsible for this chore, and where girls younger than 15 are twice as likely to carry the responsibility as boys the same age. Where does that leave time for basic schooling when basic survival is more important?

This inequality follows young women as they are pressured into families, sometimes in places with no child marriage laws and inadequate healthcare infrastructure. And when spousal abuse happens in her home, how can a woman stop the violence if her culture treats it as a normal part of a relationship with a man? Where does that leave time for secondary education? For jobs?

Together, these and other pressures pull female outcomes downward when compared with men, especially in education — one of the fundamental pillars to ending generational poverty cycles.

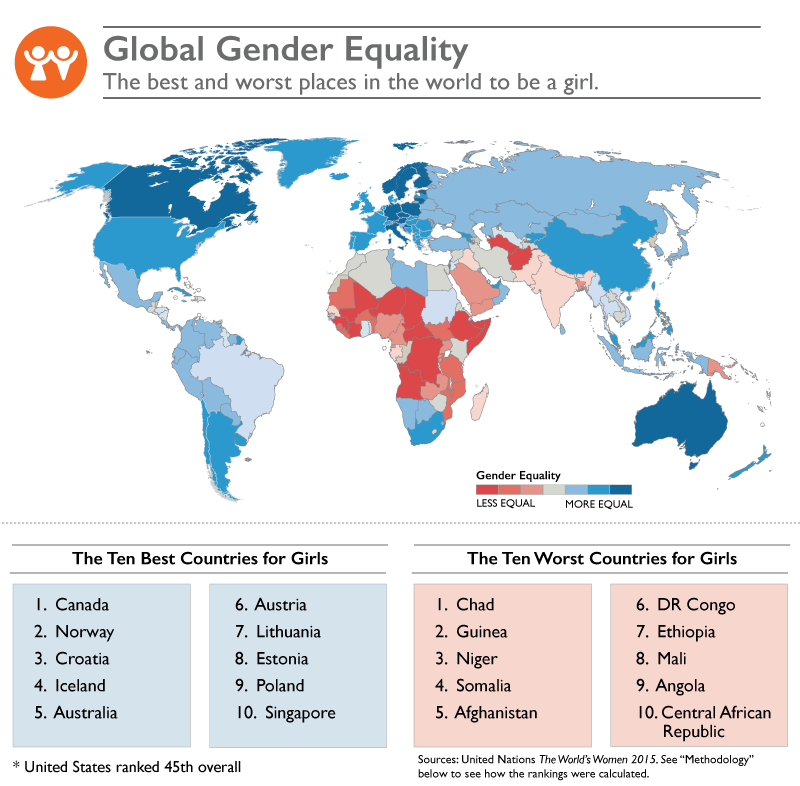

Gender inequality is most extreme in sub-Saharan Africa, even though since 2000 the region’s GDP has increased fivefold and despite a sustained demand for exports like oil. In least-developed countries particularly, infrastructure to advance women’s basic human rights is weak, partly because women are seen as the bottom of the social ecosystem and partly because of a shifting population of mostly women and children refugees. Women in some countries hardly ever see the opportunity to go to school, make an income, or own land. Domestic violence and violent crimes against women are often not classified as crimes at all, and take low priority when they are.

The worst places

Chad, Guinea, and Niger are among the poorest countries in the world and are the worst for females. Although basic laws may exist that are meant to protect women in some respects, family and religious code often override those provisions.

- In Chad, 29% of young women are married by the age of 15.

- In Guinea, 96% of women between the ages of 15 and 45 have undergone female genital mutilation.

- In Mali and Niger, more than 50% of women between 20 and 24 have had three or more children, and a majority of these women were married before the age of 15.

The best places

The best places in the world for girls are highly developed nations.

- By 2006, 84% of 19-year-old women in Canada had a high school diploma, and the percentage of women with children under 3 years old who were employed rose from 27.6% in 1976 to 64.4% in 2009.

- In Norway, although men made more on average than women in 2014, women comprised 70% of public sector employees.

- Croatia considers gender equality one of the highest values of its constitution. The country has enacted institutional efforts to maintain gender equality since at least 1996.

Education effects

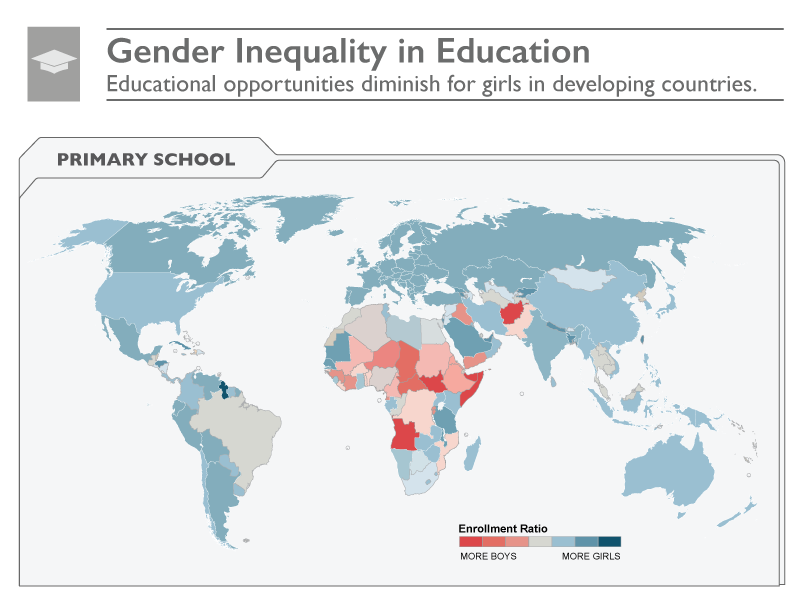

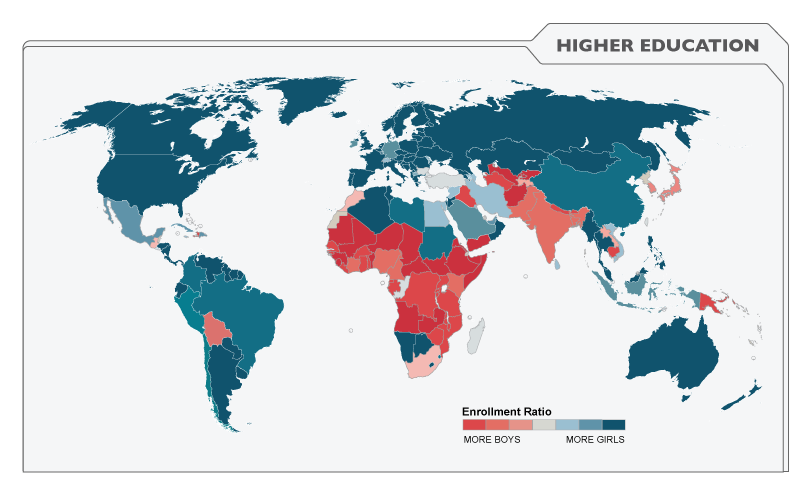

In most developed nations around the world, the ratio of girls to boys enrolled in primary schools favors girls. This ratio skews toward males in a widespread of sub-Saharan Africa countries, where basic human rights for women are not recognized. In Nigeria, 59% of girls aged 6 to 11 attend primary school compared to 65% of boys, yet inequality is still high. Pakistan and Afghanistan both have a high ratio of boys to girls in primary school and high overall inequality compared to their neighbors.

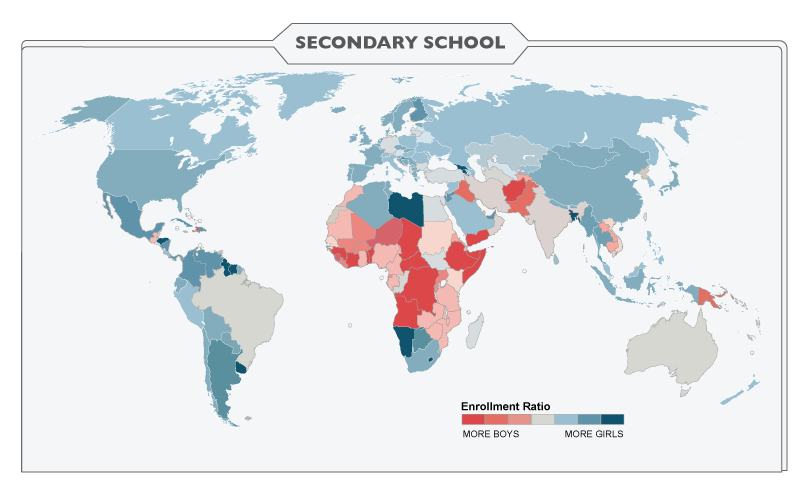

Secondary school characteristics begin to reflect the impact of societal pressure on young girls in sub-Saharan Africa. In this region in 2015, girls accounted for 55% of all out-of-school children and 52% of out-of-school adolescents. Only about 46% of girls enrolled in primary school in Chad in 2012 made it to the last grade level. In South America, the enrollment ratio consistently skews toward girls.

With college-level education, enrollment in sub-Saharan Africa skews completely toward boys, except for the Republic of Congo, where the ratio remains fairly even and where 66% of women aged 15 to 19 can read. Most of Northern Africa has more women enrolled in higher education than men. India, Nepal, and Bangladesh all have high ratios of females to males enrolled in primary school, but college is dominated by males. In these countries, women are typically married very young, but in India men and women are represented fairly equally among teachers.

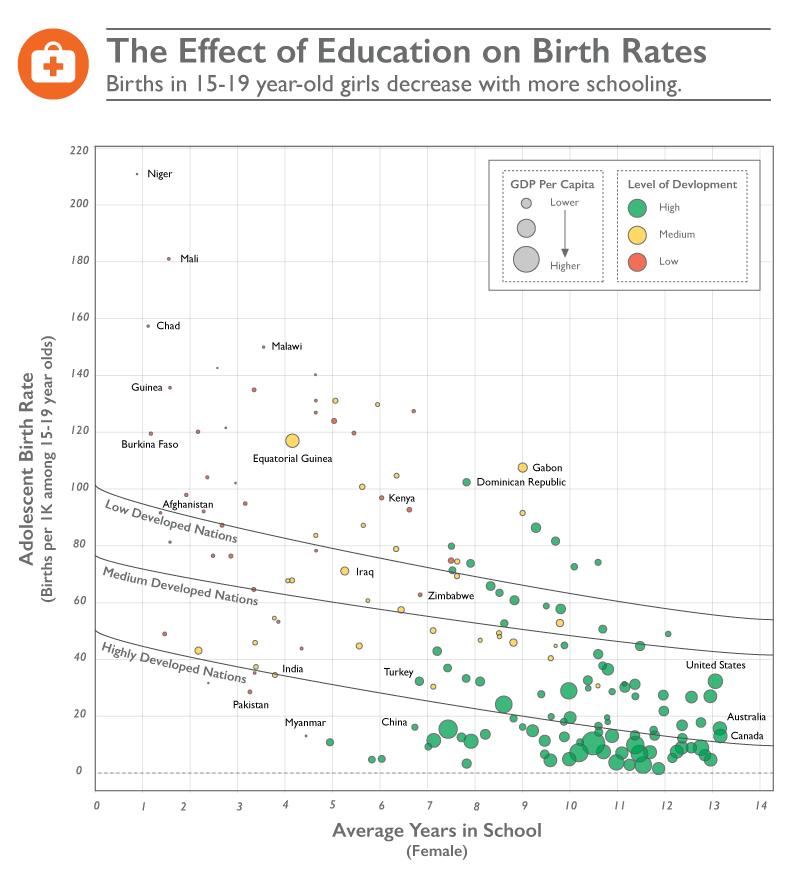

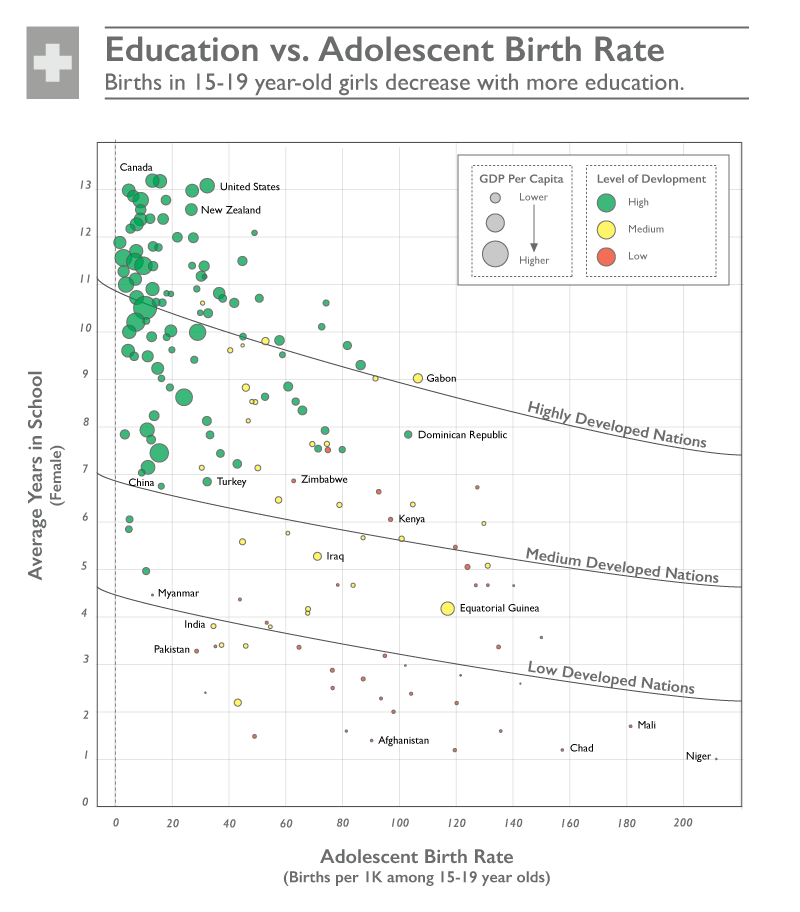

The more time that young girls spend in school, the less likely they are to marry and have children while still in their teens. Birth rates among 15- to 19-year-olds in places like Chad, Mali, and Niger are much higher than expected for such low developed nations, and they all have high rates of girls married before 15.

- In 2015, Equatorial Guinea had the 58th highest GDP per capita in the world, yet females in Iraq (roughly half of Equatorial Guinea’s GDP per capita) attended school longer on average.

- Zimbabwe, which had more than 5,700 schools in 2012, performs very well in both birth rates and average schooling for females for a low developed nation.

- Canada, the United States, and New Zealand have high average years of schooling for females and low birth rates among 15- to 19-year-old women.

After about 11 years of schooling (around the time it takes to complete secondary school) the relationship between education and birth rate levels. This suggests that factors other than time spent in school are responsible for the variations in adolescent birth rates between the most highly developed nations.

Water effects

In countries where women have to travel long distances for drinking water, there is also a high index of gender inequality. More than half of Ethiopia’s population travels over 30 minutes to collect water, and all across the Sahara region, women have very low average rates of education while comprising the majority of people shouldering the burden of water collection. Some 64% of people who collect drinking water for the family unit are women. Research shows that having to take multiple round-trips produces diminishing returns, and young girls are both more likely to be collecting water than boys and more likely to be taking multiple round-trips, too.

World Vision has engaged in community development in Ghana, and a 2015 report from the University of North Carolina showed that World Vision’s water installations have very high rates of long-term function and use. Though these efforts are only a small piece of a very big puzzle, every small step that reduces an unnecessary burden faced by a woman frees her time for other opportunities, like education.

Additionally, since 2001 the appointment of females in leadership positions has increased in the country, and in 2009 Joyce Bamford Addo was appointed as speaker of parliament, the first woman to do so in Ghana’s history. Such government representation can go a long way.

Changing the future

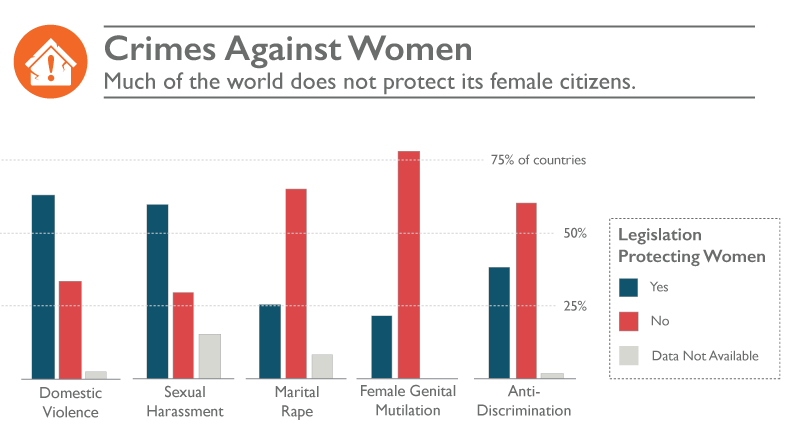

More than 50% of countries don’t have any legislation protecting women from marital rape or discrimination, and less than 25% have any legislation that protects against female genital mutilation. Although more than half of countries have legislation against sexual harassment, it is still an often underreported problem, even for women in developed nations.

Working to address gender equality in places where girls and women are suffering the most starts with a serious discussion of basic human rights. It’s not a change that can happen in a day, but countries all over the world are showing every day that inequality does not equate to in-opportunity. When given the chance and when treated with respect — the respect that human beings expect and deserve from others — anyone can thrive.

*Methodology

In 1995, at the United Nation’s Fourth World Conference on Women, governments accepted the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action. This declaration “seeks to promote and protect the full enjoyment of all human rights and the fundamental freedoms of all women throughout their life-cycle.” In accordance, the U.N. began collecting data centered around gender equality from various national and international statistical agencies. The data used in our study comes from their latest report.

To calculate our overall ranking (see graph 1) we used the same formulas the United Nations used to calculate their Human Development Index (HDI), but assigned dimensions and indicators that we believe are more applicable to girls. Our final equality index was calculated from four dimension (each containing their own indicators). These dimensions include: education, health, work, and violence.