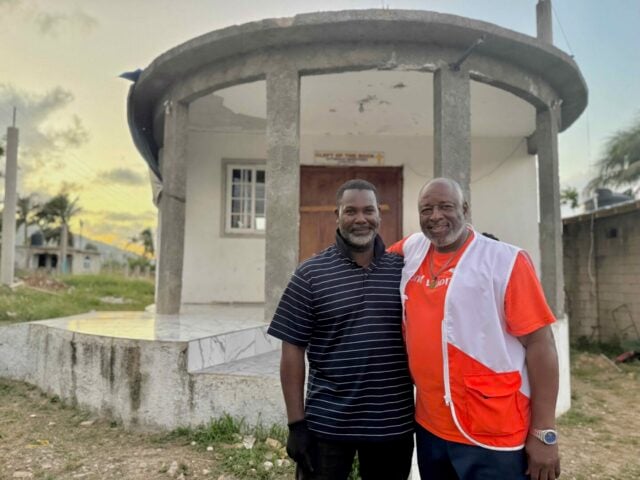

This podcast we talk with NFL lineman and World Vision Celebrity Ambassador Kelvin Beachum Jr. about faith, family, and football, as well as his trip to see water projects in Honduras. You can also read about Kelvin’s priorities in life and his passion for servanthood — specifically ending hunger.

And Johnny Cruz had a chance to sit down Washington Post syndicated columnist Michael Gerson to talk about faith, foreign aid, and going to South Sudan and the Middle East with World Vision.

Michael says his best moment as adviser to President George W. Bush was watching the president approve PEPFAR — the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief. PEPFAR helped turn the tide against the raging AIDS crisis in the early 2000s, and the bipartisan effort expressed a faith-informed belief in universal human rights and dignity.

Michael is now a weekly columnist for The Washington Post, writing about everything from politics and foreign policy to culture and religion. He has traveled to South Sudan and Lebanon to see World Vision’s work. We spoke with him about his travels and how faith-based groups can work with the government to fight poverty.

We also feature music from Haiti — from the socially conscious singer-songwriter BélO.

Prefer to read instead? Here’s an excerpt from the podcast with Michael Gerson:

How can the government work with faith-based organizations and religious communities to meet the needs of the most vulnerable people?

The ideal approach is for the government to provide the kind of scale necessary for response efforts and for churches to not just work with federal funds but also add their own element. The church’s distinctive is their concern for the whole person — body, soul, and spirit. That is something government can’t do — reach people’s deepest spiritual and emotional needs. Both the government and churches have comparative advantages, so both need to be involved.

The scale of many of these problems is much larger than the response by private and religious institutions. In an issue like the AIDS crisis, when there were 30 million people infected, saying “Let the church take care of this problem” would not have worked. The scale of the problem was too great. The response needed to be coordinated in a way where government was irreplaceable.

But the government also needs to understand that it’s often best to work through trusted private and religious institutions in providing help. Sometimes that’s a cultural challenge for people in government. They don’t understand it’s possible for religious people and those in government to cooperate for the common good.

How does foreign assistance play into that cooperative work, and why is it critical?

In government, it’s rewarding to work with officials like members of Congress to build support for these programs. It’s sometimes not an easy argument to make because foreign assistance is money that goes to noncitizens. You have to make the case why it’s necessary. I’ve enjoyed the challenge of making that argument in the private sector — that America’s role in the world does not just depend on our military power, it also depends on our moral standing. We can serve both our values and our interests by promoting hope as an alternative to hatred and promoting development as an alternative to terrorism, drug cartels, human trafficking, and many of the problems that take root in failed states, weakened governments, and bad economies.

Americans need to understand that we have a moral role and obligation in meeting these needs and promoting these alternatives. We also have an interest as a country in trying to remove the sources of conflict and violence in our world. And I’ve seen programs do that — where whole communities can be changed when they move from disease and poverty to health and hope.

Does foreign assistance actually work, and if so, how?

It can work, and it does in many cases. This is not to say these programs are perfect. But PEPFAR is one example — not just of a successful program, but a program that has changed its approach and identity at least three times to respond to the most current needs.

It began as just an emergency program: Put up tents; get people on treatment; save the lives of people in mortal danger. After that, the goal was to scale up. Then in 2008, PEPFAR shifted its focus to building health systems that were necessary now that we had redone a lot of our emergency response. The goal was to reach sustainability by building health systems. Now there’s another change aimed at effective prevention — to reduce new infections through early treatment, which makes the disease much less communicable. Resources are shifting to aggressive prevention.

If PEPFAR were a business, that would be a really good record of responding at least three times over the course of a little more than a decade to redo their approach to meet current needs. I’ve seen some of these programs that could be used as examples in management schools.

You’ve seen some of World Vision’s programs in South Sudan on one of your trips to that country. What can you tell us about your experiences there?

Sudan is a country many Americans have been interested in over the years, and South Sudan is a country that exists because of America in many ways. There had been an endless civil war between Sudan and what is now South Sudan, and the U.S. helped end it and bring about the birth of a new nation. I was there when independence was finally achieved. It had been hard fought, hard won. The country had serious development problems, but it was very hopeful.

In this case, we have seen real political digression and the growth of internal civil war. On the trip with World Vision, we saw the re-emergence of conflict — the stress that eventually became a civil war. And now, because of conflict and other reasons, they’re facing famine in South Sudan.

Often, people take interest in an issue for a certain amount of time, and then it goes off the radar screen. Sudan has been in that category. A lot of Americans were interested in the emergence of a free South Sudan. And now we’re not taking as much interest in the future of that country, though they have a lot of very serious needs. It happens too often that our attention is trendy, and that is a problem because these situations require long-term answers, long-term commitments, and long-term solutions.

What are the pitfalls of a cause becoming trendy?

The worst one is that you lose the trust of the people you’re working with in the countries themselves. When they see Americans come in interested only in trafficking or water and wells, but that interest is not sustained, they feel betrayed — and they should. A long-term, sustained commitment is the way our hosts and the people we serve measure our seriousness. It’s one of the reasons that organizations like World Vision are so important.

Another problem is getting the funds where they’re needed, not just where they’re popular. A lot of organizations have had a tough time raising money, say, for the Syrian conflict. It’s one of the greatest needs in our world, but fundraising sometimes has not reflected the urgency of what’s going on. At times there’s a mismatch between evident needs and donations to causes that go in and out of favor.

That’s another reason it’s important to listen to the voices from the field, to listen to people who are working in these countries to see where the cry of need is loudest, and to work there in sustained ways that build community trust. The ultimate goal is to be patient in the pursuit of wise policy. That’s true of government and it’s true of the nongovernmental organization world as well.

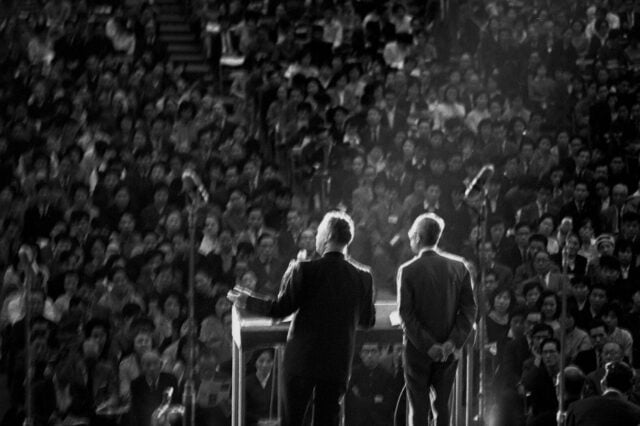

You mentioned the refugee crisis. You traveled to Lebanon with Rich Stearns to see World Vision’s work with Syrian refugees. What was the most memorable part of that trip?

One of the most moving parts was to visit an indigenous Christian church that was doing outreach to Muslim refugees. There’s been a lot of sectarian conflict in Lebanon over the years, and this kind of sacrificial service for people who are not of your own tribe has tremendous power when you see it in action. The church had converts from their outreach, but the goal was not so much conversion as it was helping people in the community.

A lot of refugees in Lebanon are not in camps. They live in between buildings and in parking lots. So when their neighbors who are of a different faith take care of them and welcome them, it does something spiritual. If people of faith are not forces of reconciliation, they’re not very useful. This should be one of the great contributions Christians bring to these situations — a spirit of reconciliation. Not just the provision of aid; the Christian distinctive should be to bring people together.

What gives you hope that conditions can improve for people living in poverty, both in the U.S. and around the world?

The source of hope I’ve seen most directly is in sub-Saharan Africa — going from 50,000 to 17 million people on treatment for AIDS because of PEPFAR and the Global Fund. I recently went to a rural clinic in Rwanda. At clinics and hospitals, I always ask to see cases related to malaria and AIDS-related opportunistic infections because I have an interest in those issues. At this clinic, I was told there are no cases. It’s because AIDS treatment in that region was universal, as was malaria treatment. Now they’re dealing with more chronic conditions instead of acute or infectious

conditions. It was a return to normalcy rather than being in the presence of an emergency. Of course, it’s not the case in every place, but it is true in some places.

That is due to the American people who supported these programs with their representatives and tax money, people who advocated for these issues more broadly, and religious partners that joined in these efforts, like World Vision. This is a victory for our country in the best sense of victory, where no one’s defeated. It’s a victory where everyone wins. I’ll never be cynical about the ability of government and the private sector to work together to solve problems, because I’ve seen it in this case.

Most World Vision supporters won’t see firsthand the work in communities around the world, yet they give faithfully. What would you tell them about the long-term impact of their support?

Being effective requires patience, commitment, and faith. Patience to give over time, because human needs are sometimes difficult and complex. And faith that human beings can be helped, that lives can be improved, that people can be saved, that children can live out full lives.

You can’t parachute into a community. You have to be there long term so people know you can be relied on and know you’re faithful. And when we are faithful, the results can be seen. We should take hope in that. I think huge problems like the refugee crisis or the AIDS crisis can be solved because I know that in every individual life, change is possible. Faith should inform the way we give, the way we support causes, and the way we, as Christians, play our role in the world.