By Kari Costanza | Photos by Jon Warren

… Rwanda was as ruined as any spot on earth after an implosion of violence killed 800,000 people in 100 days. How could the country ever overcome such hatred and horror?

It would take a miracle.

Wherever Andrew Birasa is, Callixte Karemangingo is nearby. They work side by side in the coffee fields in Nyamagabe district, southern Rwanda, talking as they weed around the berries ripening to a rosy red. The men relax together with their families, their wives and children sharing meals and guitar-accompanied songs. In church, Andrew preaches, Callixte reads Scripture, and their children dance with unabashed joy.

It is difficult to fathom how anything could come between these childhood friends. Yet not long ago, a deep hatred separated them. In April 1994, when Rwanda erupted into violence, neighbor turned on neighbor, family turned on family, and love turned to hate. The genocide turned these two friends into enemies.

This is a story about what came afterward. In war-ravaged Rwanda, where World Vision began relief and development work in 1994, hostility slowly yielded to faith and forgiveness, restoring communities and relationships.

“I like helping people. I would have become a doctor,” says Andrew, 50, sitting in his neatly kept house. Poverty had other plans for Andrew. Unable to afford college, he built himself a house near his parents in 1985. Two years later he married Madrine, now 50, and they started their family.

“During that time, I was living a great life,” he says. “I had many relatives around me and many friends and neighbors who were like a big family. Things were very good.”

Callixte, now 42, was part of the circle of friends. The two had always been fond of one another. “He was a very sharp kid,” Andrew says of Callixte. “He was very active in school. He was always number one in writing poems and singing.”

Callixte looked up to Andrew. “He was older than me, but he liked selling things that kids liked,” says Callixte. “He sold groundnuts and biscuits, so I always came to him to buy things. He was a very good person.”

Andrew says his village was a place of “peace and harmony,” where people came together for weddings and other ceremonies. Until April 1994. “Things changed all of a sudden, and people started killing each other,” Andrew says. “People had lost their minds.”

Neighbors turned on Andrew’s family. His wife, Madrine, was a Tutsi — a target for killing. Andrew tried to protect her and her relatives. “They did their best to hide,” he says. “Some even came to my house. They were discovered and killed.” Madrine survived but lost her father, mother, and five siblings.

Part of the mob that killed them was Callixte, whom Andrew had loved since childhood.

Though today they are friends, Andrew and Callixte endured a long road to healing.

Tensions had long simmered between Rwanda’s Tutsi and Hutu tribes. “The genocide was a culmination of four decades of bad politics and ethnic injustices,” explains Pastor Antoine Rutayisire, 55.

Europeans — first the Germans, then the Belgians who colonized Rwanda in 1916 — set the stage for hate. The Belgians introduced identity cards in the 1930s, dividing people by tribe — Hutu, Tutsi, and Twa, a hunter-gatherer group.

Before, all had thought of themselves as Rwandan.

Although the Hutus were the majority, the Belgians favored the Tutsis, considering them a superior tribe based on supposed physical differences. Intermarriage between the tribes muddied the waters, making it difficult to assign identity. To simplify the process, a child was classified based on the tribe of his or her father. If a person didn’t know which tribe he was from, it was determined by how many cows he owned. More than 10 cows meant you were a Tutsi.

Tutsi kings governed Rwanda until 1959, when King Mutara III died. During that year, the peasant farmers began what would be called the “Hutu revolution,” which culminated in abolishing the monarchy. The ensuing civil war between the Hutus and the Tutsis cost 150,000 lives, including Antoine’s father, in 1963.

Antoine was 5. “I know how you feel when you hate people and have to live with them,” he says.

Many Tutsis fled to Burundi and neighboring countries. By the mid-1960s, half the Tutsi population lived outside Rwanda.

Hutu leaders took power, and the government began to spread a message of hate against the Tutsis, using extremists on the radio to call upon the Hutus to attack and kill Tutsis, whom they called cockroaches.

For Antoine, being Tutsi begat blow after blow. “Every 10 years,” he says, “I had something to remind me I’m living in a country where I’m hated and taken as a second-class citizen.” At 15, he was kicked out of school. At 25, he was fired from his job. And when he was 35 — in 1994 — everything fell apart.

On the night of April 6, 1994, the plane carrying Rwandan President Juvenal Habyarimana, a Hutu, was shot down near the airport in Kigali, Rwanda’s capital. It triggered a mass hysteria such as the world has rarely seen. In the next 100 days, nearly 20 percent of Rwanda’s population would die — many by machete, blow by blow hacking away at peace, friendships, families, and communities.

One of the many scenes of carnage was near Andrew’s village in Murambi. There 50,000 Tutsis were massacred in just eight hours in a vocational school where desperate families had taken refuge. Today, the site is preserved as a genocide memorial.

The mass killing stopped when the Rwandan Patriotic Front, an army of Tutsis and moderate Hutus (led by current President Paul Kagame), seized the capital and took power in July 1994.

In the aftermath, says Andrew, “hatred developed among people in this village. Those who survived against those who killed. Those friendships that characterized this village disappeared.”

It was true of Andrew and Callixte. “I hated him,” says Andrew. “My wife didn’t have anyone left in her family.”

There were too many genocide perpetrators for the courts to try, so the government instituted gacaca courts in the villages, based on traditional Rwandan judicial principles. Villagers stepped forward to implicate the people they had seen participating in the killings. The prisons filled up with those convicted in the gacaca courts.

Andrew implicated Callixte.

Andrew reflects on the past — and the gulf of hate that separated him from Callixte.

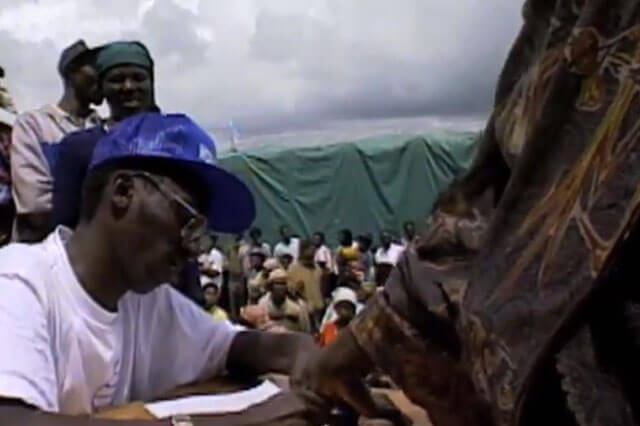

Soon after the bloodshed ceased, World Vision began relief operations in Rwanda, assisted by Antoine.

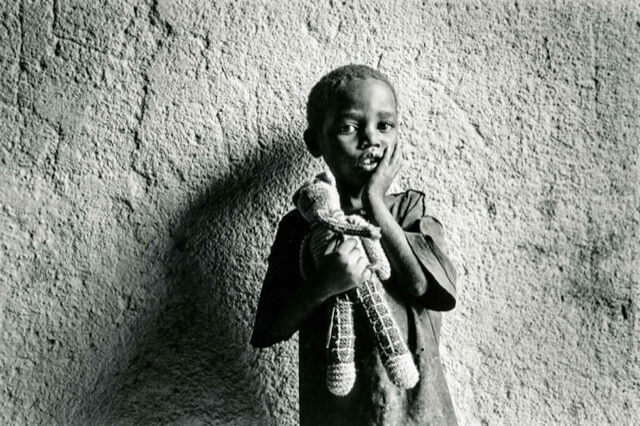

Immediately, World Vision focused on vulnerable children — an estimated 100,000 were separated from their parents. Heather MacLeod, a New Zealand nurse, worked in centers for unaccompanied children. “They weren’t playing much,” she says. “They weren’t acting like children. I have very clear memories in Nyamata of children sweeping blood out of buildings.”

In Andrew’s village, Onesphore Uwizeyimana began working with World Vision, taking care of the many orphans of the genocide. Some were babies left in the bush, hidden by their parents so that they wouldn’t be killed.

“The first thing we did was provide first aid to those children,” he says. “Some were sick because of spending hours and nights in the bushes. They were hungry. They had spent many days without any kind of food. If World Vision hadn’t helped them, many would have died.” After meeting the children’s basic needs, staff worked to locate parents or surviving relatives.

World Vision borrowed classrooms in Onesphore’s church to house the children. “They were very scared. They didn’t know what had happened to their parents,” says Onesphore, who today is the longest-serving staff member in World Vision’s Nyamagabe sponsorship program.

It was clear the children needed more than physical help. “Healing work started right in 1994, when children were showing signs of deep trauma,” says Josephine Munyeli, World Vision’s specialist for healing, peacebuilding, and reconciliation. “World Vision was assisting traumatized children who were affected by the loss of their parents.”

In 1996, when thousands of families began to return to their villages in Rwanda, World Vision started a reconciliation and peacebuilding department.

“Reconciliation was necessary and a foundation for every initiative,” says Josephine. “If we were to do development work straightaway when people had not yet dealt with their painful past, we would be heading nowhere. People carrying deep pain cannot be productive.”

World Vision developed a reconciliation model that endures today: a two-week program of sharing intensely personal memories of the genocide, learning new tools to manage deeply painful emotions, and embarking on a path to forgiveness. The approach was replicated all over the country and embraced by the new government.

“Thousands of people went through the process,” says Josephine. “More than 200 trainers were trained. Two thousand survivors and perpetrators went through healing training. And 2,000 youth went through PRAY — Promotion of Reconciliation Among Youth — which used dance, drama, poetry, and artwork to help traumatized children express their feelings.”

Sponsored children Amina (left) and Jossiane — best friends and daughters of Andrew and Callixte — tend to their families' goats. As reconciliation began to take root in Rwanda, so did World Vision sponsorship programs.

Andrew and Madrine began to hear messages of reconciliation as they worked on World Vision-supervised projects, including terracing hillsides to aid farming and rebuilding the school that was used to house Tutsis before they were killed.

Andrew reels off a long list of World Vision’s support: “They rehabilitated houses that had been destroyed. They provided shelter to survivors whose houses had been completely destroyed. They provided clothes. They provided food for people who hadn’t been able to harvest for three months.”

Callixte had gone to prison in 1995, leaving his wife, Marcella, and two young children. “I struggled,” she says. “It was unbelievable. It was the first time I’d even been alone with children to care for. They all looked at me for support, and I didn’t know what to do.”

In 2000, World Vision began the Nyamagabe development project, supported by U.S. sponsors. (Today, U.S. supporters sponsor more than 26,000 children in Rwanda.) Sponsorship funds continued the important work of healing the psychological wounds left by the genocide. The funding also provided projects to rebuild Nyamagabe — education, water, sanitation and health, economic development, and peacebuilding.

Community volunteers were needed to watch over sponsored children, reporting any health issues and making sure they are going to school. Among those who volunteered: Madrine and Marcella. They still avoided each other. Callixte remained in prison, and Andrew still resented the family.

But in spite of life’s hardships, Marcella wanted to give back. World Vision had built her a house, provided school fees and books for the boys, and opportunities for her to work. “Knowing that World Vision was supporting my children, I stood up,” she says. “I wanted to support other children in my village.”

Both Madrine and Marcella were picked as community volunteers. “[Madrine] didn’t blame me,” says Marcella. “She didn’t look at me with the bad eye. But the hatred between our husbands kept us apart.”

The gulf between the couples kept their children apart as well. Many of the children were of the same age and wanted to be friends. Andrew’s son, Manuel, remembers this troubling time. “We were forced to keep a distance,” he says. “They wouldn’t let us mix. But we wanted to play with everyone.”

Working together on projects, focusing on sponsored children, and learning about peace and forgiveness melted both women’s hearts. “At first I hated her because of what her husband did,” says Madrine of Marcella. “After training and listening in church, I came back to my senses.”

Madrine began to take food to Marcella. She took on a maternal role with the younger woman, healing through helping.

During the 13 years Callixte was jailed, he began to heal, Marcella says. “My husband changed a lot in prison. He is an artist. The songs he sang and performed affected him. He went through reconciliation workshops. At the end he felt, ‘What happened happened. I need to live a new life.’ ”

Callixte was released from prison in 2007. He came back to the village and was Andrew’s neighbor once again. With their families involved in World Vision’s programs that emphasized reconciliation, the stage was set for their reunification. But for Andrew and Callixte, the process was an arduous one.

Appropriately, the light of forgiveness shined on the families in church. “We went to church and heard the pastor preach,” says Marcella. “One day we were all at the same service. It was as if the pastor was talking to us. He looked right into our hearts. After church we said, ‘We have got to talk.’ In 2010, we got back together. Since then, we have been close.”

“Our children saw us change,” says Madrine. They watched their parents’ hatred turn into friendship. Today, their sons, Jean Bosco and Manuel, both 19, are like brothers. “He’s my best friend in life,” Manuel says of Jean Bosco.

A World Vision project featuring cows and coffee cemented the relationship between Andrew and Callixte. Villagers were given cows to raise for milk and fertilizer. The fertilizer was used to grow coffee plants. Villagers combined their plots to create bigger farms on which to grow the coffee. In every group were genocide perpetrators and survivors so that World Vision would continue to talk through the issues of healing and reconciliation.

The men, who are in a group called Good Coffee, are looking forward to their first coffee harvest. They also are starting a side business with cows, walking together to purchase cows from the market and reselling them for a profit.

Cows are now just cows, says Callixte. They symbolize nothing but opportunity. “Cows are no longer seen as a way of dividing social classes of people.”

Today, Andrew and Callixte go to prisons together, visiting genocide perpetrators who are still incarcerated and talking with them about reconciliation. Learning to forgive has made all the difference for the two friends and their families. “It has set us free, me and him,” says Andew. “It has set our families free.”

Sometimes transformation is physical: a school with new classrooms, sturdy desks, and paint still wet to the touch. Sometimes transformation happens within groups: a community learns to work together toward a common goal. But the most intoxicating transformations happen when hardened hearts change.

“You see in every country, people get wounded. People get hurt. They need to forgive. They need to reconcile,” says Antoine, who today is a pastor in Kigali, an author, and an international speaker. “Your life becomes better when you repent, confess, and reconcile.”

After working with World Vision in the beginning, Antoine chose to minister to the church. He was asked to stay on by World Vision International’s then-President Graeme Irvine, but he had other plans. “I’d like to go around and bring together pastors, build some hope, and put them back into activity,” he told Graeme.

Rwandan churches were in a terrible state. Many had been used as staging grounds for killing. There was mistrust among the congregants.

Before the genocide, more than 80 percent of Rwandans said they were Christians — which meant that many of the perpetrators thought of themselves as believers. Antoine knew the church had failed Rwandans, and he was bent on setting things right.

World Vision funded his work. “I remember the first money we used for reconciliation with churches was given by World Vision,” he says.

In 20 years of ministry in this shattered country, World Vision has provided practical aid and programs that brought people together. Sponsorship focused on children, the hope of the country. But the real progress is something that might only be detected in the laughter of friends after church on a Sunday afternoon, or the sight of children kicking a handcrafted soccer ball, or in a calm moment when wind whispers through the leaves of a tea plantation.

“World Vision has done many things in this community,” says Jonathan Gahima, an early church partner in southern Rwanda, “but to me as a pastor, the most important thing was healing people’s hearts.”

Martin Tindiwensi of World Vision in Rwanda contributed to this story.