Thriving crops fill the 31-mile basin of Antsokia Valley, in Ethiopia’s central highlands — tall stalks of sorghum and maize, delicate strands of the indigenous teff grain, trees laden with oranges. Irrigation ditches feed mountain spring water to the thirsty fields. Children go to school; the sick find relief at health centers. A lively market draws crowds who buy and sell every variety of locally grown produce and farm animal.

But people here remember what happened 30 years ago when the land drained of color and dreams turned to dust. People in Antsokia call it “those bad times.”

In the 1980s, stubborn drought exacerbated by government policies plunged Ethiopia into one of the greatest humanitarian disasters of the 20th century. Nearly 1 million people starved to death or perished from hunger-related diseases.

Operational in Ethiopia since 1971, World Vision had been airdropping food into drought-plagued communities three years before the famine hit TV screens. In fact, it was World Vision’s Twin Otter plane that helped BBC journalists break the story in October 1984.

The resulting $4 billion global outpouring was unprecedented. Life-saving help arrived from all corners: children donating coins, rock stars raising money, governments sending grain shipments, and humanitarian organizations mobilizing manpower. The surge of donations enabled World Vision to scale up relief operations from $3.5 million to $70 million and add almost 800 staff.

In the decades since, Ethiopia continued to require international food aid due constant population growth compounded by erratic rainfall, deforestation, land rights, and a host of other factors — including, this year, the influx of half a million refugees from troubled neighboring South Sudan. In January, the government reported that 2.7 million Ethiopians are acutely food insecure.

But there is good news to be found in Ethiopia today, in places where development aid funded by child sponsorship tackled chronic problems. Antsokia Valley is one such place. World Vision arrived there during the bad times and stayed as long as it took until things got better.

Meet four residents who saw it all.

Local hero

“World Vision belongs to Antsokia; Antsokia belongs to World Vision,” says Girma Wondafrash, 75. “Ask any member of the village, and that is what you’ll hear. We belong to each other.” Without him, the relationship might not have existed.

Thirty years ago, Girma was the local government representative responsible for some 30,000 people — all in jeopardy as the drought deepened. “There were eight to 10 people being buried in the same grave,” he recalls. “Children were left alone without parents to care for them. I saw a baby trying to suckle at his dead mother’s breast.”

In a place without phones and a time before texting, email, and fax machines, Girma’s only way to get help was to travel 220 miles south to the capital, Addis Ababa — first by foot, walking out of the valley to the main road, then catching a bus. It was scorching hot on his trek and he had no water, but he shrugged it off: “The people I left behind were suffering. They were my only concern.”

In Addis Ababa, he spent a week arranging for the central government to formally invite World Vision to work in Antsokia. A staff member returned to the valley with him, took photos, and left. Next, an American paid a visit — World Vision relief director John McMillin. But John’s verdict wasn’t good: His team couldn’t bring equipment and supplies into the inaccessible valley.

“What about an airfield?” Girma asked. Doubtful, John agreed. Girma immediately met with an engineer to design it. He marshaled thousands of people to contribute labor. “Even those who weren’t strong helped,” he says, describing people using their hands and feet to remove rocks and level the earth. That afternoon, just as workers added the finishing touch — white cloth flags along the landing strip — World Vision’s plane appeared on the horizon.

The airfield provided World Vision’s entrée into Antsokia Valley. By 1984, it was one of eight locations that collectively fed more than 150,000 people a day and provided medical care for thousands more suffering from the kind of diseases that prey on weakened bodies: cholera, typhoid, and malaria. “The number of people dying decreased, and people began to be saved from starvation,” Girma says.

When the next phase of World Vision’s work began, Girma proved a valuable partner. He helped provide land for a demonstration farm — a testing ground for new farming methods and crops never before grown in the valley, such as sweet potato and cabbage. It was the seeds, tools, and training provided to farmers that enabled families to fight their way back from the brink of death.

A tree nursery raised fast-growing eucalyptus for building materials and local tree varieties for controlling soil erosion. The nursery created hundreds of jobs by employing people to tend the grounds and pack tree seedlings in a special blend of alluvial soil and fertilizer, and millions of trees were planted across the valley.

“There is nothing here that World Vision hasn’t done since then for the community,” says Girma. “During the rehabilitation period they provided every kind of agricultural input — improved cattle, improved seeds. They’ve constructed schools. All of the children who weren’t going to school are now attending.” He notes that some graduates have gone on to work in government offices.

Now people come from all over the world to see the vibrant life in Antsokia Valley — and to meet the man whose initiative saved his people. Looking back, Girma says he never gave up. “I had trust in God that he would help me. If I failed, my people would perish. It was God who helped me.”

Model farmer

Abebe Aragaw has made a name for himself with his fruit crops. His mangoes, papayas, and bananas are always in demand in Antsokia’s market and in those of neighboring towns. “I’ve learned how to grow these fruit trees and how to manage the land and protect it,” says the man in his 50s, who is dressed more like a businessman than a farmer. “I nurse these plants like they’re my family.”

But he vividly remembers the past: “In 1984, you would never see anything like this farm. Even trying to grow seedlings, it wouldn’t have been possible. Everything was very, very dusty — totally unlike this.”

Back then, Abebe was a young father of a 2-year-old daughter, Yeshi, who had grown so thin “I could count her bones.” He and his wife brought her to World Vision’s feeding center, where the child improved, but his marriage failed. “It was hunger that made us separate,” he says. “[My wife] thought we wouldn’t have a normal life.”

While his daughter recovered, Abebe took a job guarding the feeding center’s entrance. Work of any kind was precious, but what he saw on the job still haunts him: “Many, many people were pressing against us, competing to get into the center for help. They were desperate, very hungry — we couldn’t manage them; there were too many to let in. So as I watched, they died in front of me, their bodies dropping to the ground.”

In time, he found more satisfying labor on World Vision’s food-for-work projects. He helped build a bridge over the Borkena River, which solved a chronic problem of river flooding cutting off key access routes across the valley.

Then World Vision agronomists chose Abebe as one of five model farmers. He received tools and seedlings and learned how to grow tomato, cabbage, coffee — and the fruits he’s known for today. He built terraces to plant trees. Through a government resettlement program, he obtained more land to expand his farm. And he remarried and expanded his family.

Thanks to his success with farming, Abebe’s children enjoy the advantages he never had, such as education. They also thrive on a varied and balanced diet. The difference between the food he had for his first child, Yeshi, and for the other children born later is stark. “When Yeshi was young, there was no such thing as fruit and vegetables like this to feed her — it was only traditional maize and soy gum,” he says. “Now that I have plenty of different fruit and vegetables, my children feed on different types of things. They’re healthy — I see that.”

Back in 1984, Abebe went to the feeding center believing it was all over — he and his family would never survive, never go home. He thought it would never rain again and nothing would ever grow. But his story has had a different, amazingly better ending. “It’s really incredible the change that I’ve seen from the famine,” he says. “I’m really grateful.”

Determined mother

“I remember the time of the famine — the sun flared, there were no trees,” says Ansha Hussein. “It was so dusty that the dirt blew around us in a whirlpool.”

The youthful smile of this woman in her 40s belies a hard past. Her family, like so many others, suffered in 1984, forcing them to the feeding center for help. Ansha, who was about 10, carried one of her siblings on her back.

Everyone feared for the youngest. “My brother, Ahmed, was so thin that he was like the size of my little finger,” she says. “We kept on asking ourselves, Will he die? It was difficult to even feed him because he struggled to open his mouth. His skin was loose, hanging off his body.” At the center, Ahmed was given red status — the critical group.

Ahmed pulled through, but the newest member of the family was not so fortunate. “My mother gave birth at the camp,” Ansha recalls. “She woke me up as she went into labor, and my sister was born healthy. But because my mother didn’t have any milk to feed her, three days later, [the baby] died.”

Ansha’s mother, weak with hunger and disease, didn’t have the strength to hold her newborn. “It was me who first hugged the baby,” says Ansha. “She wasn’t named. We didn’t expect her to survive — or indeed any of us. We were all waiting for our deaths.”

Around her, other families’ tragedies played out. Ansha saw a dying woman calling out for each of her children, over and other. People’s lives leaked away with diarrhea and vomiting. “I was very young to see such things,” she says.

Though her parents and siblings recovered, nothing got easier for Ansha. “It is our culture to get married young to a person we don’t know,” she explains. Her parents married her off at age 15, to a man with kidney disease who was often ill. And memories from the feeding center haunted her dreams.

But as conditions improved in her community, Ansha’s fear began to melt away. “World Vision saved our lives with its work,” she says. “Most children were supported with feeding, and when people were sick they were treated in the health clinics. When people were feeling better they received a sack of flour so that they could return home with something to eat.”

With World Vision’s help, there were schools, and before she was married, Ansha loved learning to read and write. But when she became a wife she had to drop out. Her determination to succeed academically shifted to her four children, two of which were assisted by World Vision child sponsorship.

“I really regret stopping school at grade five,” she says. “Because of that, I really want my children to be educated and highly qualified. My first child has finished high school and is now in college learning nursing. My dream is for my children to be doctors and to continue studying until their master’s education.”

Ansha, now a widow, manages her own plot of land on which she grows sugarcane, grains, tomatoes, and cabbage. She sells two truckloads of sugarcane each year. The rural area where she lives has no electricity, but World Vision helped her set up solar power for her house. She wouldn’t dream of marrying her daughters young and discourages others from the practice.

“I use the events of 1984 to counsel my children,” Ansha says. She shares with them her optimistic outlook that if it hadn’t been for the drought, World Vision wouldn’t have come to provide new crops, technology, water systems, and child sponsorship.

“Sometimes they see the challenges of my life and they want to drop out of school to help me. But I tell them that compared to my childhood, this is nothing.”

Son of World Vision

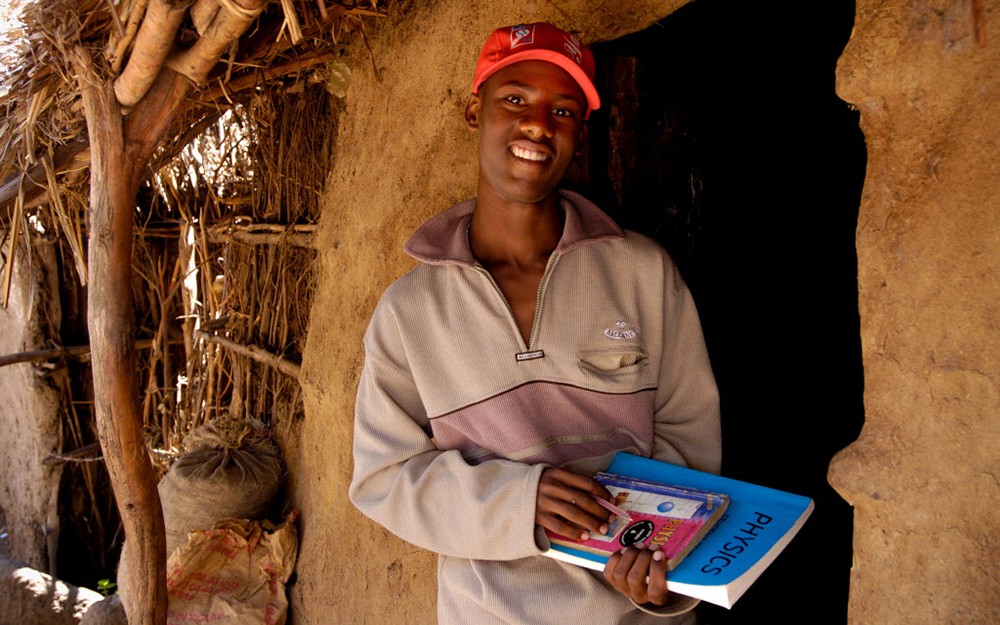

Emmanuel Tamene exemplifies all that is possible for the children who were born into post-famine opportunity in Antsokia Valley.

Not that the 27-year-old entirely missed out on hunger. His parents, Tamene and Zewdie, were poor, and meals were often meager. “Sometimes I couldn’t perform well at school because I didn’t have enough food to eat,” he says. “If you have nothing to eat tomorrow morning, what do you think about as you do your homework? It’s painful.”

But he knows he had it easy compared with his older sisters, who nearly died in 1984. Zewdie took the two unconscious, extremely thin girls to the feeding center and waited in agony with her two other children. She recalls, “I kept praying to God to have their health restored and to bring them back to my safe protection. I was so very happy when they were returned to me healthy. I thanked God for their survival.”

Zewdie describes her joy at seeing the girls revive and become playful children again: “They were sick with no hope, and then they were well with hope.”

World Vision helped the struggling family with food and a job for Tamene, first as a security guard and then in the tree nursery. Zewdie had three more children — the first, Emmanuel, received sponsorship assistance “from the start of school until his university graduation day.” For Zewdie and Tamene, who have only three years of schooling between them, this was an accomplishment beyond imagination.

“From the beginning,” Emmanuel says, “I always dreamed of working as a health professional and helping the sick. I knew what it was like living in poverty, so I wanted to help as many of these people as possible.” After graduating with a bachelor’s degree in health sciences, he joined the staff of the government district hospital and worked with HIV-positive and malnourished patients. Next he joined Medecin Sans Frontiers, a medical humanitarian organization.

“I am an example of how sponsoring a child has such impact. I consider myself a son of World Vision,” Emmanuel says. “Sometimes donors don’t know what happens with their donation, but there are so many children who benefit from World Vision.”

He likes being a model of success for Antsokia children, although now there are plenty of highly educated people around, and Emmanuel hopes that World Vision will construct more schools so that the trend continues.

Still aiming high, Emmanuel bubbles over with plans for his future: “I want to study more — engineering, astrophysics, and the like. I want to be involved in humanitarian activities, particularly those helping children. I want to establish a clinic for under-5s [children].” He’s considering a move to Addis Ababa to achieve these dreams.

Even if he leaves the area, Emmanuel hopes World Vision won’t. “World Vision is in all of our hearts. It’s the jewel of Antsokia Valley.” The organization has phased out some programs in order to expand into surrounding communities.

And yet the verdant valley promises to be a permanent reminder of the transformative power of faith-based development work, carried out by committed staff and community members who caught the vision. In the words of the late Dr. Ted Engstrom, World Vision’s president in the 1980s: “Antsokia became a model for other organizations of what could be done in a barren patch of valley.”

Georgina Newman contributed to this article.