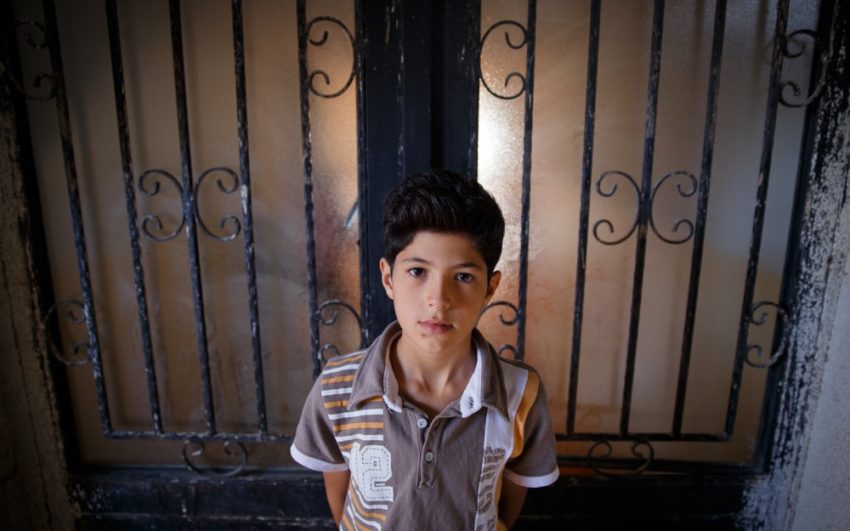

Ahmad is an astute 12-year-old boy who loves school, and he is a Syrian refugee living in Lebanon who is fortunate enough to attend school for free. After years of constantly moving around in a foreign country, the ability to go to school provides normalcy. This is no small gift to children like Ahmad.

In September, Lebanon’s government announced it will provide schooling to 200,000 Syrian children, but another 200,000 Syrian children will not have that opportunity. More than 4.2 million Syrian refugees live in Lebanon, Turkey, Jordan, Iraq, and other countries in the region. Officially, about 1.1 million live in Lebanon — one-quarter of the country’s population — but the number is likely much higher, according to local aid workers.

Ahmad and his family have lived in Lebanon’s Bekaa Valley for more than three years after the civil war in Syria drove his father to find work in Lebanon. But soon, escalating violence forced the rest of the family to also flee Syria.

Despite the ongoing turmoil, Ahmad has found a sense of stability as he attends school and spends time at a World Vision Child-Friendly Space. These activities help Ahmad to think forward, dreaming of how he wants to be a doctor someday. And as he reflects on the pain and difficulty of his disrupted life, he keeps it matter-of-fact, as if it’s merely a distraction.

Relatively fortunate

Ahmad lives in a two-room apartment with his parents and three younger brothers, a one-minute walk to the World Vision center and, ironically, about an hour’s drive from their former home in Damascus, Syria.

This is the third home his family has had in Lebanon. They are relatively fortunate; they have a kitchenette and one small bathroom, and their landlord is flexible and compassionate toward the family. But the ceiling leaks, and there’s nothing to do around the house, he says.

His father earns about $400 per month, Ahmad says. Rent eats up $300 of that. So they barely scrape by after stretching to buy food, basic household necessities, and transportation to school. The hardest thing since leaving Syria has been finding a reliable place to live, Ahmad says.

Soon after the Syrian war broke out in March 2011, Ahmad’s father moved to Lebanon to find work to support the family.

They tried to make it work living in Damascus, but the violence became unbearable, so they moved to their farm outside the city. They endured the insecurity for a year before bombs started exploding on their farm too.

His mother decided to flee to Lebanon only after the tension, fear, and longing to see their father became too much for one of Ahmad’s younger brothers, who pleaded to reunite in Lebanon.

A place to be happy

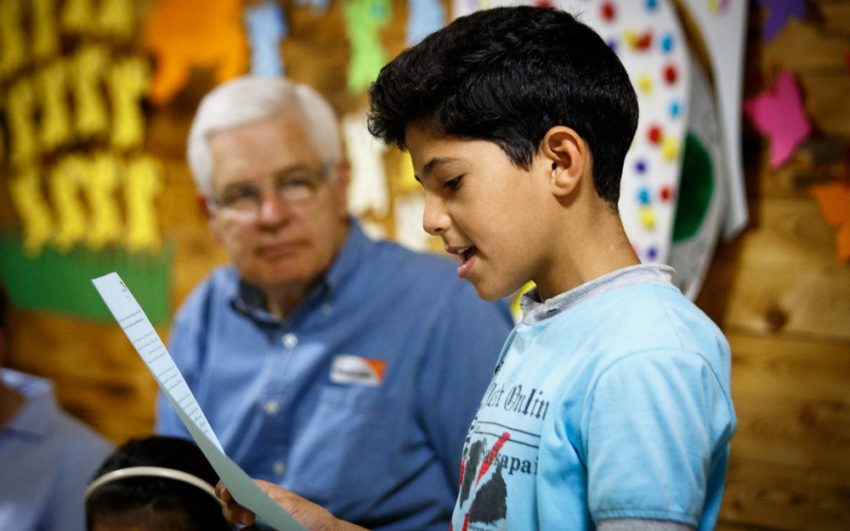

Ahmad and some of his friends are glad to be among the half of Syrian refugee children who are able to go to school.

After school, four days a week, he and his best friends, Ahmad and Omar, come to the Child-Friendly Space to play and participate in various crafts, like drawing, painting, and other activities. He likes everything about the time he has here.

The boy is thoughtful but somewhat reserved — but his eyes light up when he talks about his studies and the joy of getting time to play with his friends.

“We come here to be happy,” he says.

Nearly 1,000 Syrian children come to World Vision’s Child-Friendly Spaces throughout Lebanon. Most of them do not attend school. Those who do often complain of difficulties learning in a new language and of being picked on by resident students. So this is the one place where they get to play games, socialize, and learn — to detach for a moment from the harsh reality of life as a refugee.

Another nearly 300 children attend World Vision’s early childhood education program, which provides a more formal classroom setting for younger children.

The centers have been open to Syrian refugee children in the Bekaa Valley since 2012.

World Vision Project Manager Christine Mdawar says, “(We) have witnessed cases of children with traumas, “learning difficulties, and social difficulties overcoming their particular weaknesses and becoming more enthusiastic to ride the bus, attend the Child-Friendly Space, and participate more with teachers and classmates.”

While children prepared to board the bus home one October afternoon, Ahmad sits at a table in a classroom near the center’s front entrance. Teachers and students congregate in the hallway as sunlight beams through the open streetside door, and the bus rumbles and squeaks to a stop.

Ahmad says he loves school. But if he couldn’t come to the center, “I wouldn’t play. I would be at home. I wouldn’t be happy.”

He explains that he and his friends wanted peace back home as anyone else would. He wants to be happy more often. He wants stability so he can study and pursue his dream of becoming a doctor and helping people.