Traditionally, the hard work of a community has been left to adults. But in western Honduras, one boy isn’t waiting to grow up to serve his community.

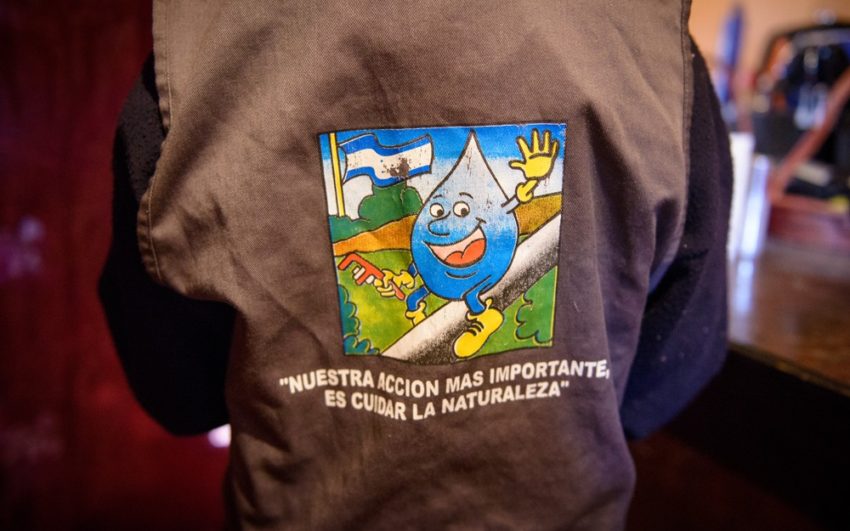

Selvin Garcia slips on a khaki vest with a smiling water droplet on the back and, grabbing a clipboard, joins World Vision staff member Emilio Dominguez on the dusty, red clay roads of Yamaranguila, western Honduras.

Walking with determination from house to house, Selvin checks off his list: Are animals penned up away from water sources? Are family members washing their hands after using the latrine? Is the home kept generally clean?

This is ordinary work for a health volunteer. But 12-year-old Selvin isn’t ordinary. His involvement in these activities proves that development work isn’t just for adults. In fact, often a community’s most powerful resources are its children.

In Yamaranguila — and around the world — World Vision equips young people to play important roles in strengthening their community. For Selvin, it didn’t happen overnight. “I stopped being shy, so I was able to speak up to say what I think,” he says. “I feel that I have grown a lot, and it was World Vision that awoke this.”

Papi to the rescue

In his dozen years, Selvin has experienced more than his share of tragedy. He never knew his father, who went to work in another country when Selvin’s mother, Glenda, was pregnant with Selvin. After he was born, Glenda worked long hours to make ends meet, and at times the young boy did not see his mother for days.

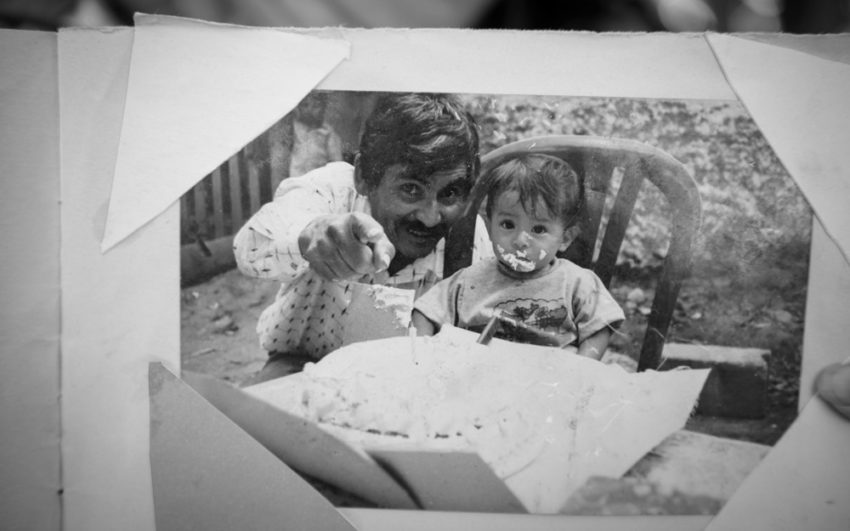

The bright spot in his life was his grandfather, whom he called Papi. The family’s photo album memorializes Selvin and Papi together: Papi, wearing a cowboy hat carrying a young Selvin in his arms; a bright-eyed Papi pointing at the camera, encouraging a bewildered 1-year-old Selvin, his face smeared with frosting, to smile.

The album holds no photo to remind Selvin of the time he fell out of a tree. But Selvin remembers the accident clearly — Papi was right there to rescue him, even though it was time for Papi to be at work at the telephone company.

Once Papi was sure Selvin was fine, he urged the child to stay out of the tree: “If you fall, all right, I’m going to stay, and I’m going to help you. But then I could lose my job, and we need my job to help the family.”

His words were prophetic. That same year, Papi did lose his job. Increasingly, he was forgetting things.

“It was very difficult for us,” Selvin says, “because most of my uncles were already studying at the university. So when he lost his job, they had to quit the university and start working.” When Selvin turned 6, the diagnosis came: Papi had Alzheimer’s disease.

On top of this grief, Selvin’s great-grandmother passed away. When the news reached Selvin’s father, he flew into Honduras’ capital city of Tegucigalpa. Home was a three-hour drive away. “As he was coming on the road, there was a truck that was coming the other way,” Selvin says. “The truck moved sideways, and my father crashed and fell into a ravine.” He died there, never seeing his son.

Selvin has a photo of his father. “I remember that the first time I saw that photo, I cried,” says Selvin. “I said to myself, ‘Why did he have to die the same year that my grandfather got sick, that my [great] grandmother died. Why did it have to be that way?’”

Something good happening

Subtract Selvin’s tragedies, and Yamaranguila still isn’t an easy place to grow up. The area is home to the Lenca ethnic group, which includes Selvin and his family. Previously, the people suffered from high rates of acute respiratory illness, fueled in part by open fires and dirt floors indoors. Tiny bugs living in the thatched roofs of homes spread the heart-swelling Chagas disease. The high elevation and colder climate left families struggling to eke out meager crops on steep hillsides dotted with los pinos — pine trees.

World Vision introduced child sponsorship here in the mid-1990s as a way to care for all Yamaranguila children. To provide new opportunities, staff set to work training parents to raise family income and literacy through economic empowerment. As their assets grew, parents were equipped to provide a more secure future for their children. Core to that security is that children can attend school — and not have to drop out to work.

Norman Sanchez, World Vision’s manager in Yamaranguila, says World Vision bases its work on the needs of the people: “We teach them to dream with their feet on the ground.”

World Vision also works directly with the community’s children — those who have sponsors and those who do not — nurturing youth in self-esteem, gender equality, and children’s rights. Boys and girls are equipped to help peers who are struggling in school. To ensure children have a stake in their community’s progress, World Vision also invites young people to join the children’s basic sanitation committee. Members share the sanitation messages they’ve learned with other children, and these messages ripple outward in ever-increasing circles.

Little did Selvin know that this children’s committee would transform his confidence — and his future. Frustrated as his grandfather’s health continued to deteriorate, Selvin decided to become a doctor. “I wanted to know what was happening to my grandfather. I thought if I study a lot maybe I [could] find a cure to his ailment.”

Selvin joined the children’s basic sanitation committee, learning about the importance of handwashing, teeth brushing, and other hygiene practices. He worked hard in school, and his stellar grades paid off in a way he never imagined: His teacher recommended him to World Vision’s local youth training programs. “That was a really great day for me,” says Selvin. “I said, ‘Well, my grandfather is sick, but at least I have this that is so good [happening] to me.’”

World Vision’s spiritual nurture also helped alleviate Selvin’s grief over the loss of his loved ones. “I got very near God,” he says. “I thought, ‘I know they are with God and they are going to be okay.’ And when the day comes that I am together with them, we are all going to be a family.”

‘I’m the protector’

On a cold morning, smoke from the open-fire stove circled in the Garcia kitchen. Soot stained the corner of the mud and straw walls above the stove. A single bulb overhead offered little light, but a ray of sunshine streamed through the kitchen’s only window.

Selvin kept a scarf wrapped around his neck as he bustled across the kitchen’s dirt floor. He pulled a small bit of cornmeal dough from a big blue plastic bin, patted out thin tortillas, and dropped them on the griddle. The fire didn’t heat the stovetop quickly, so the eggs scrambled slowly. He stirred a warming pan of beans at the same time.

Selvin dropped pieces of tortilla into a bowl, added the eggs and beans, and garnished the meal with a few pieces of avocado. The breakfast was for his 4-year-old half-brother, Lester. Selvin watched as Lester ate, and then he prepared breakfast for himself.

His culinary skills grew out of his experience with World Vision’s basic sanitation committee. “I learned about how things had to be cooked clean,” says Selvin. With his newfound knowledge, Selvin questioned whether the food they ate was prepared properly. At the age of 7, he decided to learn to cook.

His first cooking adventure wasn’t so successful. He dropped parts of the eggshell into the pan. But in time, he improved. Now on most mornings, Selvin can be found making breakfast for Lester.

“I’m the protector for my little brother,” Selvin says.

He’s also become a protector of his peers. “Life here in my community is very harsh,” he says, pointing out that many children are forced to sacrifice school to harvest coffee.

As his grades climbed, Selvin also decided to help friends who struggle in school — some who had repeated a grade more than once. He asked his teacher about the tutoring program World Vision offers, and soon he was working with two students. He’s proud to report that both students advanced to the next grade.

Selvin likens this accomplishment to saving someone hanging from a cliff, helping them to be the person they are meant to be. “Maybe this person could have become a doctor, maybe this person even could become president of the republic,” he says.

Community caretaker

When Selvin isn’t using his clipboard to monitor the community’s health practices, he often can be found behind a table outlined with ribbons of green tissue paper. Straw, pine needles, and moss also decorate this tabletop tableau of Yamaranguila.

His community model features cardboard houses sporting straw roofs. A church wears its hand-cut cross like a crown. Plastic orange tigers, pink lions, and brown dogs stand in for chickens, cows, and goats.

“This model represents Yamaranguila before World Vision arrived,” Selvin says of the miniature village he built with the help of World Vision staff members. He launched into his presentation without hesitation.

He flips one straw-covered roof, then another to reveal the new tin corrugated roofs that now grace Yamaranguila homes. He explains that before World Vision began working in his community, the houses made of mud, clay, and straw bricks used to have thatched roofs. Now the tin roofs don’t house the bugs that transmit the deadly Chagas disease.

Before, latrines were scarce. Now, most houses have them, he explains, carefully placing miniature latrines in his model.

“The animals would hang out in the river. And those rivers are where families would get their drinking water. That’s where they would wash their clothes. That wasn’t hygienic,” Selvin explains.

He puts the lion, tiger, and dog inside a pen made of Popsicle sticks. Now the once-polluted water source can remain uncontaminated and people can stay healthier.

He finishes with a flourish: “All this is what World Vision has done for Yamaranguila. And not just for Yamaranguila, but also around the world. Our Yamaranguila has changed. It’s not the same. It’s a stronger Yamaranguila. A better one.”

Emilio Dominguez, who provides training to the community’s youth, says Selvin is a bright boy. “We feel very proud of him because everything that we teach him, he will replicate in his community. I have to say that he even does this better than the technicians themselves.”

Someone to hold his hand

For years Selvin enjoyed the community benefits of sponsorship without having a sponsor of his own. Then one day that changed.

Two years ago, Selvin presented his community model to visitors from the United States. One of them was so taken with the boy that he asked to sponsor him. Selvin was delighted. “Wow, there is this person who wants to hold my hand and wants to help me,” he recalls.

Selvin, who loves to give hugs, says that if his sponsor were with him right now, he would hug him and tell him that he loves him dearly. “I really want him to know that I keep him deep in my heart. I always carry him with me, and I hope he does [with me] too.”

The steadfast support of World Vision’s child sponsors ensures the transformation of young people like Selvin. Always the explainer, Selvin describes how this works.

“The sponsor sends the seed. World Vision is the farmer who plants it, and that yields fruit. I am the fruit of that seed. And thanks to World Vision who planted the seed, it has awoken the fruit inside of me,” says Selvin. “I know that there are other children who have also been awakened and are that fruit as well.”

The sponsor sends the seed. World Vision is the farmer who plants it, and that yields fruit. I am the fruit of that seed.—Selvin

Even though he has lost many people in his life, Selvin has found others willing to support and propel him onward to become the best person he can be. He knows now the power of finding his voice. He knows how it feels to be a spokesperson for his community.

But he also knows too much about sorrow. He despaired as he watched Papi decline to the point where he no longer recognized Selvin. Last year, after Papi passed away, Selvin placed a Father’s Day card on his grandfather’s grave. For this tender young man, it was a moment of great sorrow.

But purpose gives him hope. There is still much work to be done in Yamaranguila. He has committee meetings to attend, house visits to make, and presentations to give. At home, Lester will be waiting for breakfast. Maybe there’s a letter from his sponsor waiting there too.

Dana Cruz of World Vision’s staff in Honduras contributed to this story.