Food, water, and shelter from the elements are requirements for survival. Without them, a serious conversation about human rights can’t exist, even on World Human Rights Day, Dec. 10. For what good are human rights if there are no humans around to live out those values?

On a global scale, children today have a much higher chance of survival than they did half a century ago. Widespread vaccination against preventable illnesses and stronger prenatal and post-natal care have helped significantly. But more progress is needed.

More than 360,000 children under 5 die each year from complications due to unsafe drinking water, according to the World Health Organization. On top of this, it is expected that by the end of the next decade half of the world’s population will be living in water-stressed areas, meaning there will even be fierce competition for unsafe drinking resources.

The issue of basic human needs becomes more complex when geopolitics and social systems are layered into the discussion. A United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees global trends report showed that roughly half of all refugees in the world were younger than 18 in 2015. Who is accounting for the child who became separated from her parents while fleeing the place she calls home?

We have looked at the rights and opportunities for girls around the world. Now we turn our lens wider to understand the perspective of any child, boy or girl. Where is it easiest to survive into a mature young adult? Where are children struggling? And what can we do about it?

The worst places for children

CHAD

Nearly 30% of children in Chad between the ages of 5 and 14 were working in 2010 because Chad lacks the infrastructure to combat child labor and exploitation. In 2014, 78% of youth 15 to 24 years old had not completed primary school — despite it being offered for free by the government. A child’s parents also sometimes shoulder the burden of paying for some of their teachers’ school supplies and salaries. Plus, pressure from Boko Haram has closed many of the country’s most available schools, making it even more difficult for children to get a basic education.

What is World Vision doing?

World Vision has been working in Chad since 1982, providing training for mothers to reduce infant mortality, improving water sanitation, and providing food and medicine for people affected by drought. In addition to child sponsorship programs, World Vision has also provided communities in Chad with educational programs to fight malnutrition and medical equipment to deal with malaria and other disease outbreaks.

SOMALIA

Somalia is one of the poorest countries in the world, and 39% of children ages 5 to 14 there were working in 2006. Child trafficking for labor and sexual exploitation are not criminally prohibited in Somalia, which has a weak legal system, so children are often targets for recruitment to military and terror organizations. In addition to being targeted directly in their schools — places where children should be safe and free to learn — school facilities are often occupied by military forces and, in some cases, are damaged beyond use.

What is World Vision doing?

World Vision began working in Somalia in 1980 — helping refugees fleeing the conflict between Ethiopian and Somali troops. Since then, we have provided food, tools, medicine, education for mothers, and repairs to wells and water pumps throughout the country. Today, World Vision continues to develop partnerships focused on reducing child mortality and improving access to clean drinking water. According to UNICEF, about 45% of the country had access to an improved drinking water source in 2015.

SOUTH SUDAN

About 46% of children aged 10 to 14 were working in South Sudan in 2008, mostly in agriculture. South Sudan also has had problems addressing the recruitment of child soldiers despite existing programs designed to curb the practice. In addition to high infant mortality and poor access to safe drinking water in schools, children who do reach the end of their compulsory education around age 13 are faced with a unique situation: They are not required to go to school but have little to no legal work opportunities. This makes them particularly susceptible to trafficking and exploitation. A combination of poor infrastructure, sporadic attacks on schools, and armed conflicts that involve children make it more difficult for children in South Sudan to live into adulthood.

What is World Vision doing?

World Vision’s work in South Sudan began in 1972. To help vulnerable people displaced by civil war and fleeing its atrocities, World Vision has provided food, cooking fuel, and shelter to more than 50,000 people. South Sudan has continued to suffer from widespread armed conflict that targets children, and World Vision fosters relief efforts designed to keep families together. Today, World Vision supports immunization activities, helps build and fortify schools, and advocates for reliable access to clean water. We also provide support and psychological recovery for more than 100,000 children; South Sudan has a high population of children leaving militaristic lifestyles. Although the country’s average income went down between 2008 and 2012, neonatal mortality has dropped significantly despite continued conflict.

ANGOLA

Diamond mining, an industry known to subject children to poor working conditions in underground environments, is prevalent in Angola. The country has weak laws around the sexual exploitation of minors, and it’s not yet clear whether programs designed to thwart child trafficking are effective. Around half of all children that attended primary school in 2011 completed this level of education around the age of 12; but they are not legally allowed to work until age 14.

What is World Vision doing?

World Vision has been working in Angola since 1989 — providing food and agricultural tools and training to combat hunger. Raising HIV and AIDS awareness among the country’s population has been an important priority for nearly two decades and continues to be a focus. Much of World Vision’s work today in Angola also prioritizes improving healthcare and opportunities for rural families through sustainable education programs.

What else impacts children? HIV and AIDS

The Child Health Index is a useful starting point for considering other aspects that might impact children and their livelihoods, like HIV and AIDS. For example, about 11% of orphans in Angola have lost one or both of their parents to complications due to AIDS. A child in this situation will have a hard time attending school, especially if they have no other family or access to an orphanage. If such a child does not succumb to starvation or disease, he or she is more likely to fall into forced labor or exploitation to survive. Living and working in dangerous, poor conditions significantly hampers children from escaping poverty, and thus overall reduces potential opportunities for that community.

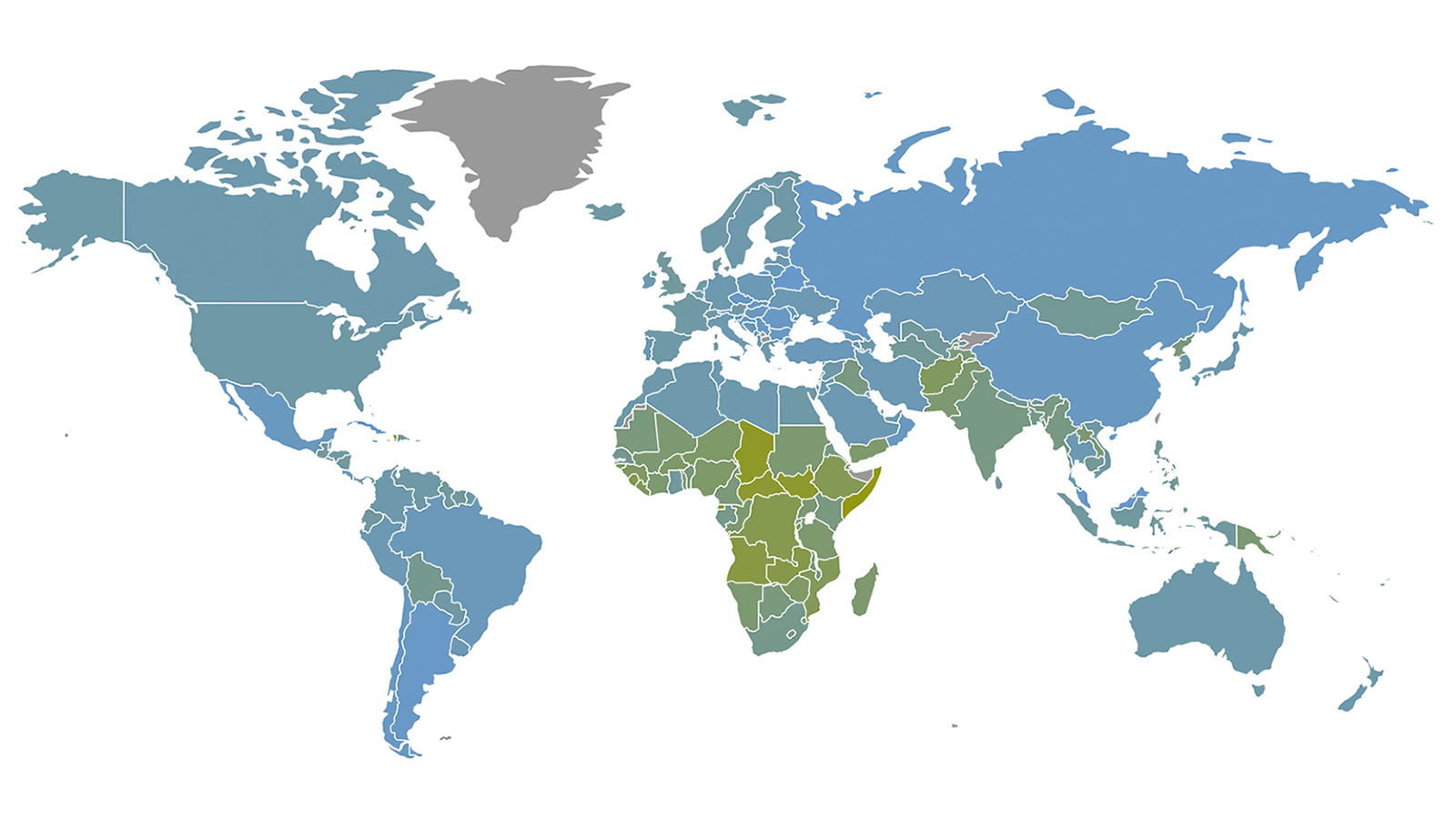

In this map, we have overlaid and transitioned between our Child Health Index and the prevalence of HIV and AIDS in people between the ages of 15 to 49 in 2011. In northern Africa, there appears to be a trend where a low prevalence of HIV and AIDS favors children’s survival.

The dark gray circles overlaid on each country show the primary school dropout rate between 2008 and 2011 among primary schools. Northern Africa continues to show strong numbers: Dropout rates are lower where the Child Health Index is favorable and where the prevalence of HIV and AIDS is comparatively low. Dropout rates tend to be higher in places where the Child Health Index is low, suggesting that even if a child survives beyond his or her fifth birthday, the potential for chronic illness can take a heavy toll on the ability to complete school.

Stand up for human rights

If we strip away the complexity of modern society, beneath these layers we are all the same. We all have fundamental human rights. We all have basic needs.

For the children of the world — the people that will grow into new generations with unique perspectives and life experiences — more progress is needed to equalize the basic opportunity for each child to live another day. The time is now to take a stand for humanity.

*The Child Health Index used for this discussion is a combination of a variety of different indicators including the mortality rate for children younger than 5, vaccination rates for six different vaccines, and the prevalence of undernourishment, with mortality weighted as the most significant indicator. The index attempts to account for data sparsity by scaling certain quantities based on availability and consistency. This index should not be used to stack or rank countries against one another, as some of the data used in its calculation is not normalized. Instead, the index and its change over time are better used to analyze a specific country’s situation relative to itself. The coloring is designed to show conditional similarities between countries, not to show that one country is “better” than another. We developed the Child Health Index using raw data from the World Bank database.