Although we often discuss poverty in terms of dollar amounts, money is only the beginning of the conversation

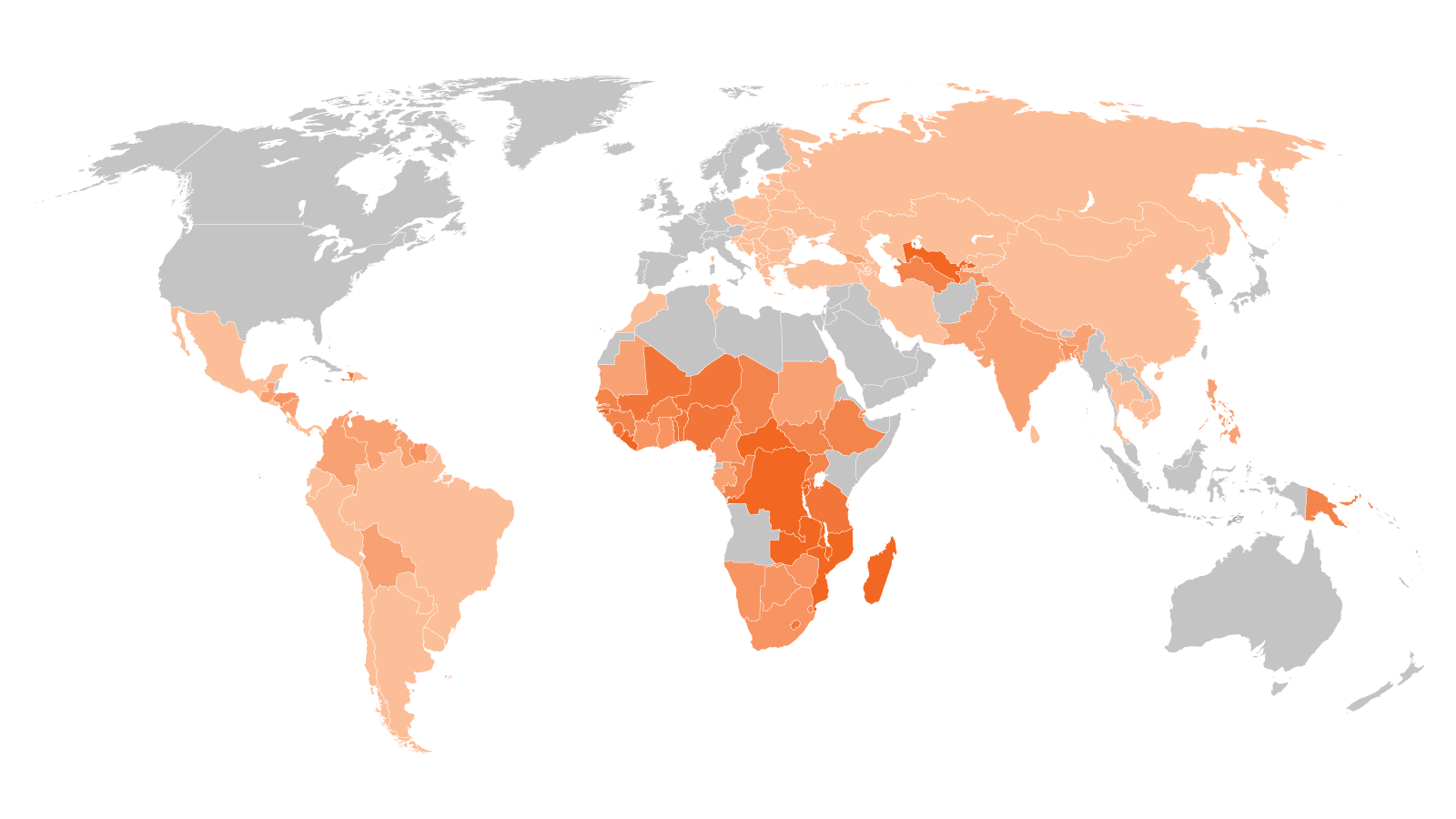

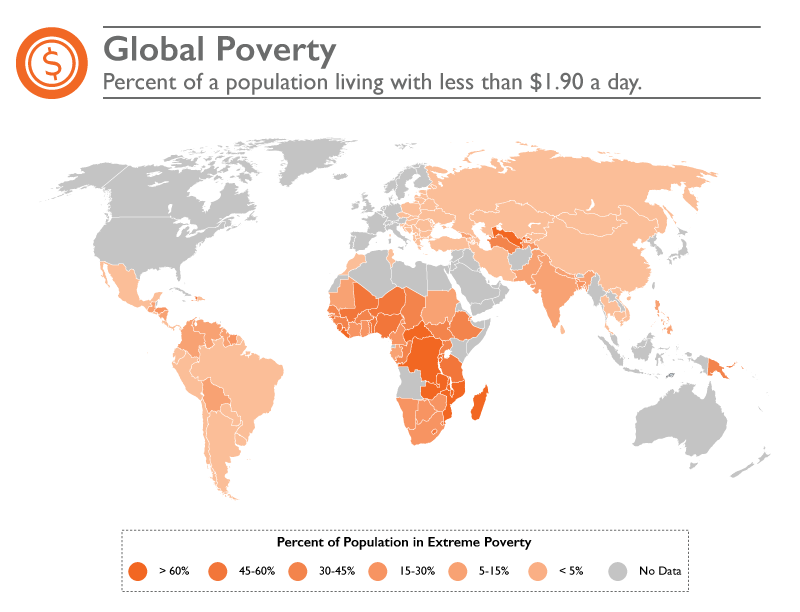

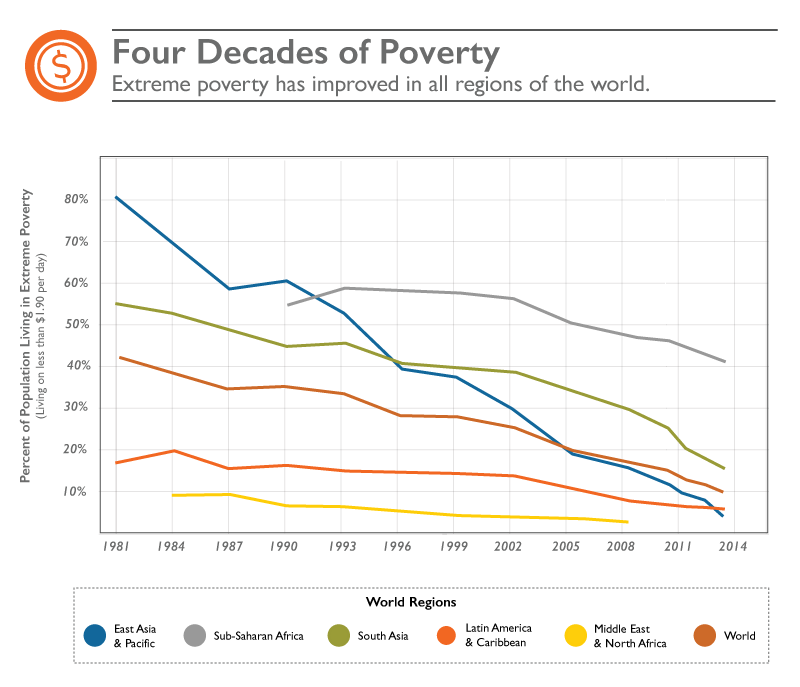

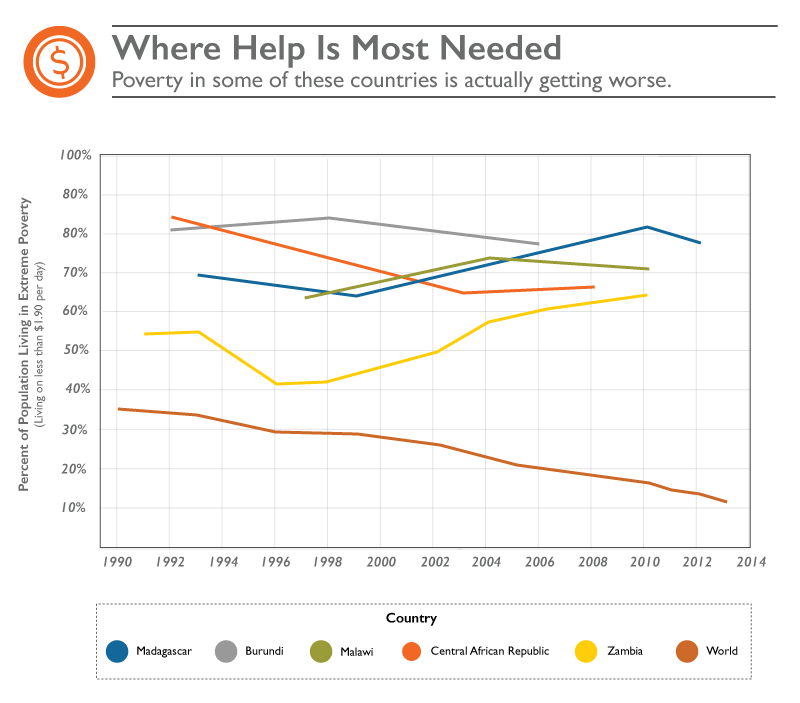

As a whole, the world has made large strides in reducing extreme poverty. In 1990, 35% of the world’s population was living on less than $1.90 a day, according to the World Bank. Today that number is 10.7%, a nearly 25 percentage point reduction. There are a lot of complex explanations for this decline: globalization, widespread ideological change, and a warm post-war climate focused on productivity and improvements in health are only a few.

But what is $1.90 a day for an individual? Typically, it means a life of struggle. It means little to no access to school for children in poor families. It means not being able to afford a doctor — ever. It means no electricity, and in many cases, no food on the table. In the poorest countries where many people lack access to clean water and sanitation, it means the spread of preventable diseases and the unnecessary death of children to starvation and water-related diseases.

The good news is that the world has not become complacent. We can look to regions that have reduced their poverty significantly for clues on how to accelerate change in places that are suffering the most today.

The highest instances of extreme poverty are in sub-Saharan Africa. It is not a coincidence that this region also suffers from high rates of gender inequality and poor conditions for child survival compared to the rest of the world. Basic opportunities for survival directly impact a community’s ability to remove itself from poverty, and its children need to grow up healthy in order to learn and apply their education toward its improvement. The sub-Saharan region has made progress in reducing extreme poverty, thanks in part to modernization, foreign aid, and a reduction in civil conflict, but the pace is comparatively slow to other regions.

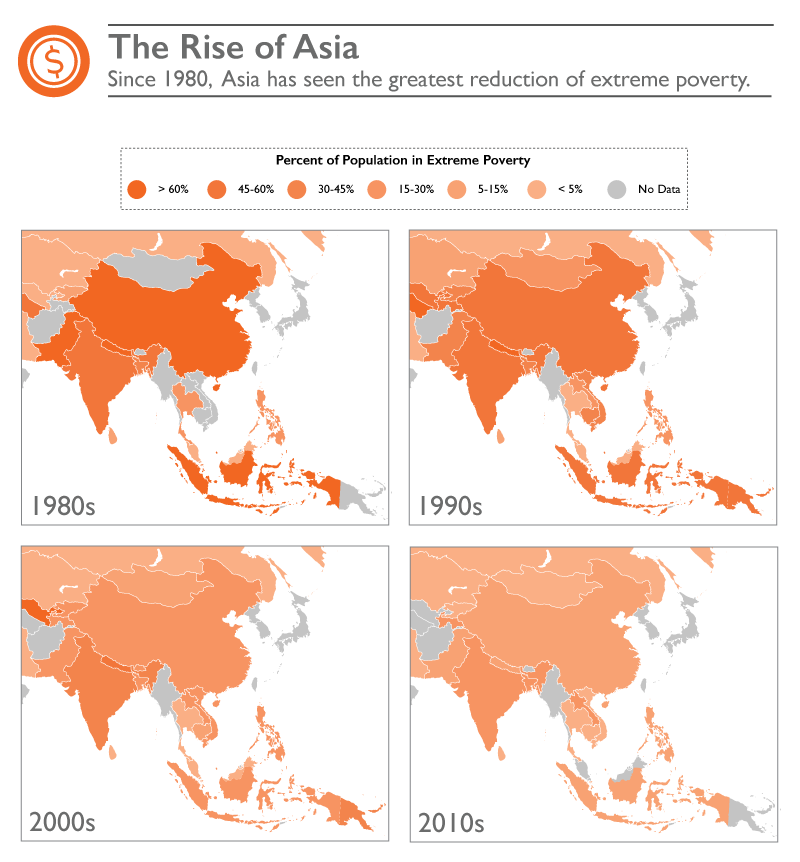

Nowhere in the world has there been a greater reduction in poverty than in East Asia and the Pacific. In the last 35 years, the poverty gap in this area decreased to 3.5% from 80.5% in 1981. This reduction in poverty was accompanied by an overall spike in the region’s total population enrolled in primary school, a persistent and upward growth in GDP and population, and strong growth in life expectancy at birth.

Such a trend is explained in part by economic inclinations toward globalization, technological adaptation, and human resource development. Though not necessarily widespread over the entire region, efforts to improve working conditions and develop rural areas have contributed significantly to reductions in poverty. East Asia and the Pacific is also a region abundant with natural resources that continue to remain in demand. Nepal, Vietnam, Cambodia, Indonesia, and China have all made stand-out improvements in the last 35 years.

Indonesia

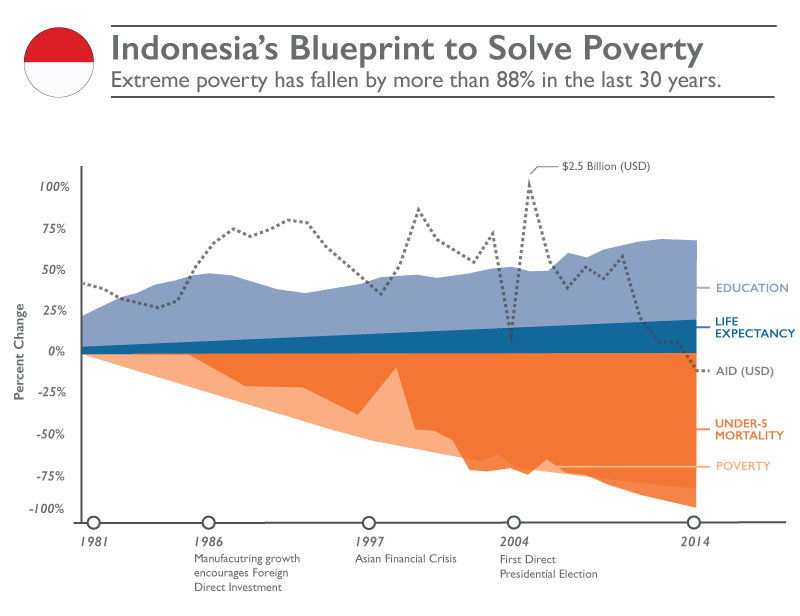

Although hit hard by high poverty rates due to the 1997 Asian financial crisis, Indonesia has since recovered and is today a part of the G20, an international forum for the governments and central bank governors from 20 major economies. In 1998 the country’s second president resigned, which led to the opening of the country to foreign aid and a strengthening of workers’ rights by allowing unions more freedom to organize.

A rise in primary and secondary school enrollment rates, life expectancy, and dramatic reductions in under-5 mortality and poverty all coincide with an increase in official development assistance and foreign aid received by the country. Indonesia has suffered violent political transitions in the past, but a stable government, the steady flow of foreign support, developing and improving workers’ representation, and a focus on fixing infrastructure have all had a profound effect on reducing poverty in the country.

Ethiopia

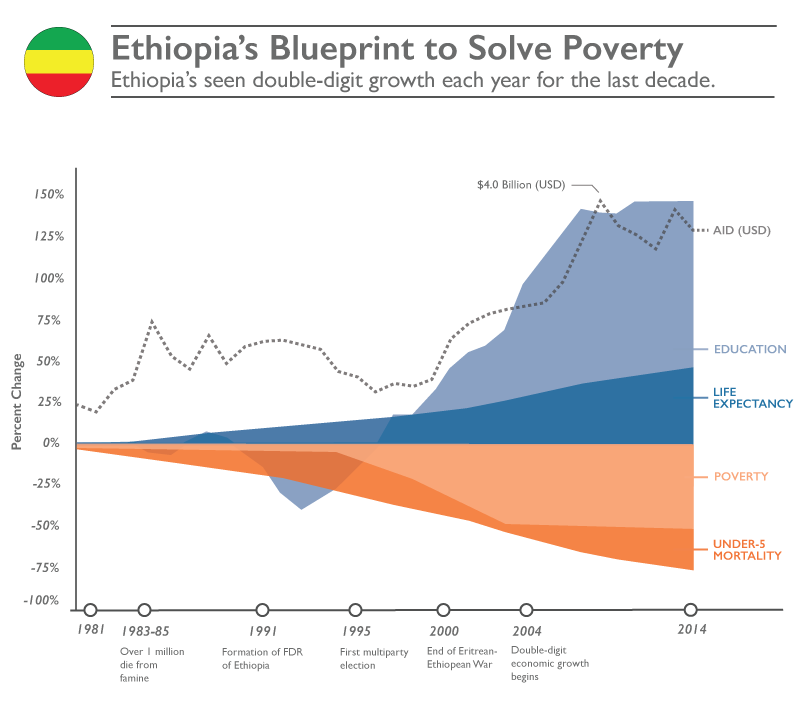

Ethiopia has also had success in reducing poverty despite a history filled with political unrest, civil fighting, and a drought that killed more than 1 million people between 1983 and 1985. Throughout the nineties, beginning with the establishment of the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, government stability and increased access to foreign aid have helped propel the country forward. Even though the Eritrean-Ethiopian War began in 1998 over disputed border territory, primary and secondary school enrollment rates in Ethiopia rose sharply. Poverty and under-5 mortality both showed steady downward decline after that year.

After the end of this border conflict in 2000, a very large increase in foreign aid received by Ethiopia coincides with the most dramatic decrease in poverty seen there since decades prior. The ensuing combination of foreign aid and political stability have helped Ethiopia achieve greater than 10% year over year growth in GDP from 2004 to 2014. The country had the fastest GDP growth rate of any country in 2015 at 10.2%.

Workers’ rights are still a concern in Ethiopia. It has no minimum wage, vulnerable children find themselves in forced labor situations, and it is comparatively difficult for workers to gather in strikes, even though they have the legal right to do so. About half of the country’s population is younger than 18, which means it has a large population that will be entering and transforming the workforce into the future.

Where is help most needed to end poverty?

Burundi, the Central African Republic, Madagascar, Malawi, and Zambia all have poverty rates that appear to be on the rise. In many of these places, the political situation is not entirely stable, and violence between political and religious factions continues to strain these countries’ abilities to focus on economic growth and developing infrastructure. Malawi and Zambia both have high prevalence of HIV and AIDS among their populations. Generally, low life expectancies at birth put additional weight on the shoulders of already-ailing populations in the fight to improve poverty.

Though every country’s economic situation is nuanced in its own ways, it is clear that societal stability is one of the most important factors in helping populations overcome poverty. Stability means better relationships with foreign partners, which means higher chances for aid, better schooling for children, and better overall expectancy for life. When countries focus less on internal fighting and more on strengthening internal programs that foster education and health, poverty tends to decrease.